Groundwater recharge approaches in arid and semi-arid regions play a crucial role in the conservation of water and the avoidance of depletion of existing aquifers. For example, groundwater is the main source of agricultural demand in the California Valley. However, groundwater storage in California has declined by about 3 km^3/year over the past few decades, with much greater declines during the droughts of 2007-2009 and 2012-2015. Managed aquifer recharge can reduce existing overdrafts by recharging excess flows to aquifers. Results show that groundwater recharge methods can restore 9–22% of the existing groundwater overdraft in the California Valley based on a 56-year simulation (1960–2015) (Alam et al., 2020).

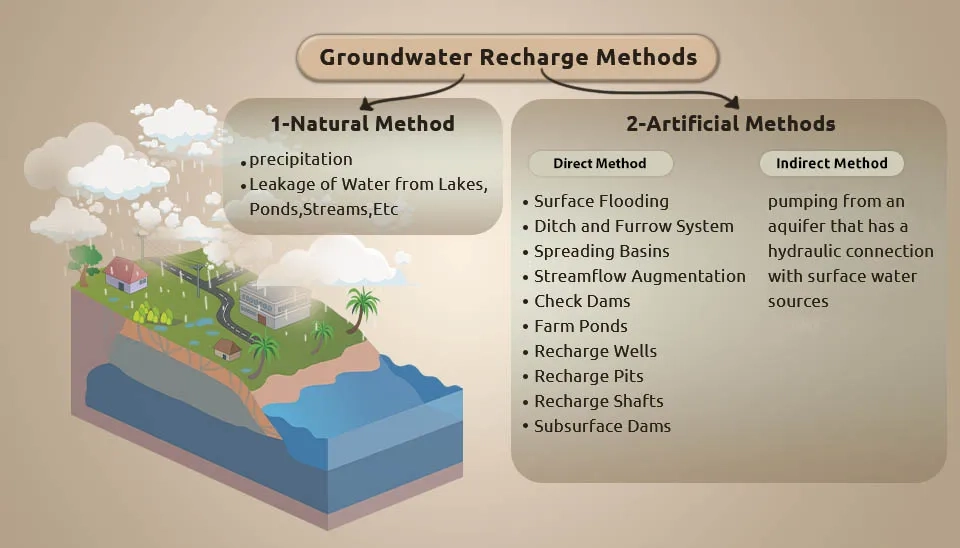

The movement of water from the earth's surface into subsurface areas is a hydrologic process that helps improve the water table at ground level. This process of water movement in a downward direction is said to be groundwater recharge deep drainage or deep percolation. Groundwater recharge techniques could be achieved either by natural groundwater recharge or by artificial methods that involve anthropogenic processes. The groundwater recharge methods are influenced by various factors, such as climate, land surface and biosphere processes, and characteristics of the unsaturated and saturated subsurface.

Although groundwater recharge techniques are one of the most important components in groundwater sustainability studies, they are also one of the least understood, largely because recharge rates vary greatly in space and time and are difficult to measure directly. Several types of water are used for groundwater recharge methods: surface water from rivers, stormwater, and treated wastewater (Zomlot et al., 2015).

1. Natural Groundwater Recharge: The Baseline Process

The natural groundwater recharge involves precipitation on soil, which enters into the soil. The other form of natural recharge occurs when there is a leakage of water from lakes, ponds, streams, etc. The water is able to move underground through the rock and soil due to connected pore spaces (Mohan and Pramada, 2023). This downward movement of water through different soil layers is called percolation. Some types of soils allow more water to infiltrate than others, depending on the soil’s permeability. During natural recharge, water is first pulled into the zone of aeration, where a mixture of water and air fills the pore space. Then the water further travels downwards to the zone of saturation—where the pore spaces are filled by water. The upper boundary of the zone of saturation is known as the water table (USGS, 2016).

The overall effect of urbanization on recharge depends on the number, type, and extent of each alteration of the watershed and on basin characteristics, such as the climate, geology, and topography of the watershed.

2. Artificial Methods

In areas where groundwater is utilized faster than its natural replenishing rate, the man-made recharge method becomes a necessary option for balancing the water levels. Artificial recharge methods are the practice of increasing the amount of water that enters an aquifer through planned and human-controlled means. The purpose of artificial recharge methods of groundwater has been to reduce, stop, or even decline levels of groundwater; to protect underground freshwater in coastal aquifers against saltwater intrusion from the ocean; and to store surface water, including flood or other surplus water, imported water, and reclaimed wastewater for future use. These artificial methods involve various techniques (USGS, 2019).

2.1. Direct Method

This method of groundwater recharge is basic and the most widely used. Under this method, stored surface water is directly conveyed into an aquifer without infiltration, and it naturally percolates through the unsaturated zones of the soil profile and joins the groundwater table.

2.1.1. Surface Flooding

Only land with a 1 to 3 percent slope can undergo recharge via flooding. The objective is to spread the water over a large area in a thin film that travels slowly downhill without disturbing the soil. The water is spread over the land surface from several distribution points to obtain an even application. Embankments or ditches may bind the system to localize infiltration or to protect adjacent land. Excess water may be collected at the system's topographic low point for disposal. In general, infiltration rates are highest where soils and vegetation are undisturbed. The biggest problem with the flooding technique is containment. The large required land area and evaporation pose additional problems. The method's greatest advantage is the relatively low cost of construction and maintenance (Alam et al., 2021).

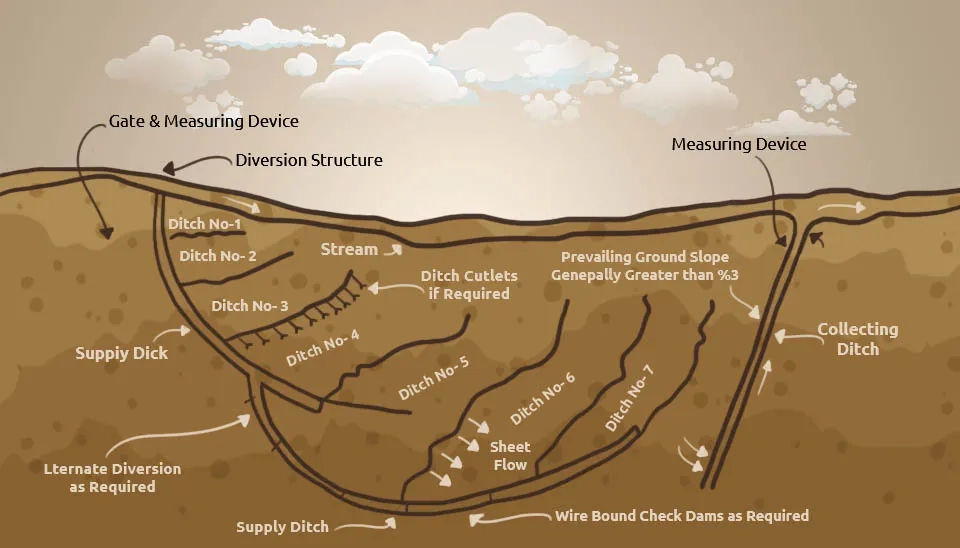

2.1.2. Ditch and Furrow System

Ditches and furrows are point or linear structures that allow for the recharge water to infiltrate into the aquifer underneath. In areas with irregular topography, flat-bottomed, shallow, and closely spaced ditches and furrows provide the greatest water contact surface for recharge water from a source or channel stream. A ditch system is designed to suit topographic and geological conditions that exist at the given site. A layout for a ditch and flooding recharge project could include a series of trenches running down the topographic slope. The ditches could terminate in a collection ditch designed to carry away the water that does not infiltrate to avoid ponding and to reduce the accumulation of fine materials. Clogging is the main cause of declining recharge rates in this type of facility (Gale et al., 2002).

2.1.3. Spreading Basins

We also refer to spreading basins as percolation ponds or infiltration ponds. Basins are probably the most favored artificial recharge method because they allow efficient use of space and require only simple maintenance. Basins are either excavated or are enclosed by dikes or levees. Basin geometry is flexible, allowing construction to be adapted to the terrain. Basins may be constructed individually, such as in small drainage areas to collect urban runoff or in series for the infiltration of streams or stormwater. The use of multiple basins for infiltration stream water provides several advantages: the storage capability allows a longer time for recharge; the upstream basins act as clarifiers for those below, and the ability to bypass the basins permits periodic maintenance (such as scraping, disking or scarifying) to restore infiltration rates. In flat areas, basins are more costly to construct because natural landform containments cannot be used; basins in such areas are commonly long, straight, and narrow and are constructed side by side.

The infiltration capacity of basins can be improved by soil treatment, vegetation, or special operation procedures. Soil treatments generally consist of adding chemicals or physically altering the infiltration surface to increase available pore space for infiltration. Vegetation creates root channels that loosen the soil and promote percolation. Scheduling sufficient rest periods for the basin between flooding periods allows drying and biodegradation of clogged layers. Periodic deep ponding helps increase basin water levels to reduce surface clogging (Bradshaw and Luthy, 2017). The advantages of basins include

Expected flows can generally be accommodated by constructing basins of appropriate size.

Intermittent floodwater can be stored for later infiltration

Clogging can be easily mitigated through basin construction techniques

The land is used efficiently.

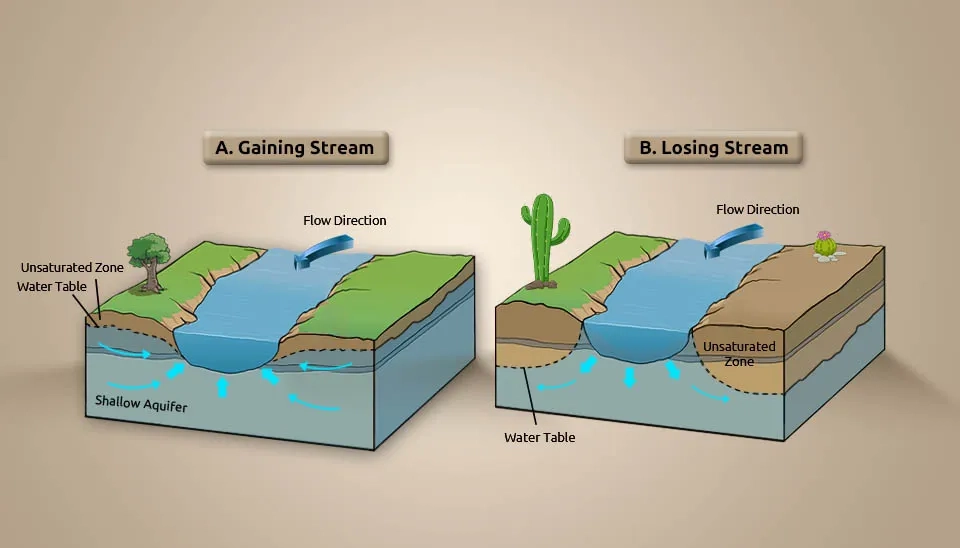

2.1.4. Streamflow Augmentation

Streamflow augmentation involves the application of recharge water to a stream channel near the head of its drainage area to reestablish or increase infiltration through the stream bed. Streamflow augmentation is considered an alternative to artificial recharge in areas where streams fed by groundwater have ceased to flow or have become dry in their upper reaches because of lowered groundwater levels. In addition to recharging, the stream environment is esthetically less efficient than other techniques because stream velocities exceed infiltration rates, and economical sources of recharge water are not always available. However, the restoration of the stream ecosystems through this form of recharge partly offsets these disadvantages (Ronayne et al., 2017).

2.1.5. Check Dams

Recharge Check dams are small barriers built across the direction of water flow in shallow rivers and streams to slow the movement of water and encourage groundwater recharge. In arid or semi-arid regions, the rivers flow only for a few days in a year (nonperennial rivers). Hence, large amounts of rainfall reach the sea as runoff and also result in flooding during peak rains. An increase in contact time between the impounded water and the riverbed will facilitate the infiltration of water in the groundwater zone, which otherwise would have been lost as runoff. Therefore, this method is especially beneficial in regions in which runoff is much higher than the natural recharge. Check dams are one of the methods of managed aquifer recharge to augment groundwater storage (Djuma et al., 2017).

2.1.6. Farm Ponds

These are traditional structures in rainwater harvesting. Farm ponds are small storage structures that collect and store runoff waste for drinking as well as irrigation purposes. As per the method of construction and their suitability for different topographic conditions, farm ponds are classified into three categories, such as Excavated farm ponds are suitable for flat topography, while embankment ponds are suitable for hilly and rugged terrains. Selection of the location of farm ponds depends on several factors such as rainfall, land topography, soil type, texture, permeability, water-holding capacity, land-use pattern, etc. (Velmurugan et al., 2018).

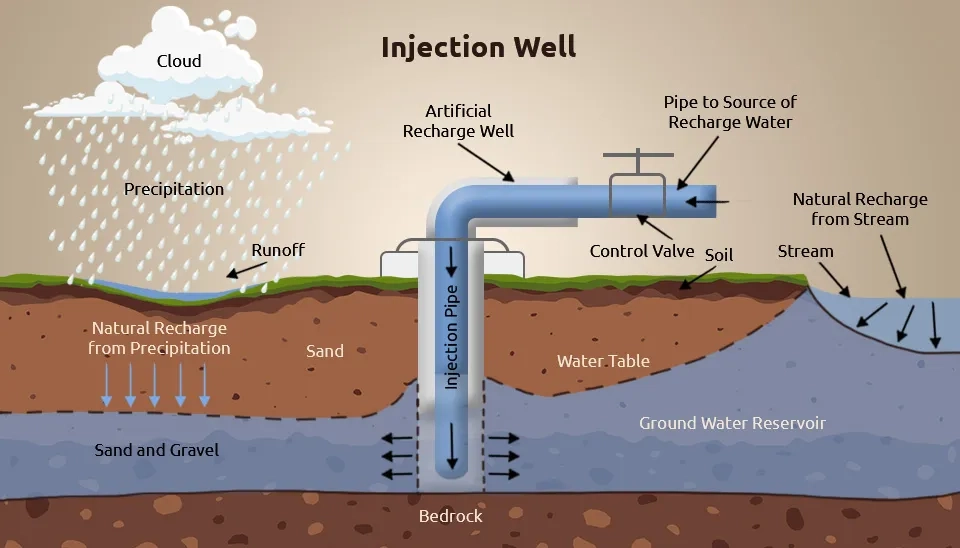

2.1.7. Recharge Wells

Recharge or injection wells are used to directly recharge the deep-water-bearing strata. Recharge wells can be dug through the aquifer's overlying material; if unconsolidated, a screen can be placed in the well in the injection zone. Recharge wells are suitable only in areas where a thick impervious layer exists between the surface of the soil and the aquifer to be replenished. Artificial recharge of aquifers by injection wells is also done in coastal regions to arrest the ingress of seawater and to combat the problems of land subsidence in areas where confined aquifers are heavily pumped. A relatively high rate of recharge can be attained by this method. Clogging of the well screen or aquifer may lead to an excessive buildup of water levels in the recharge well (Ghazavi et al., 2018).

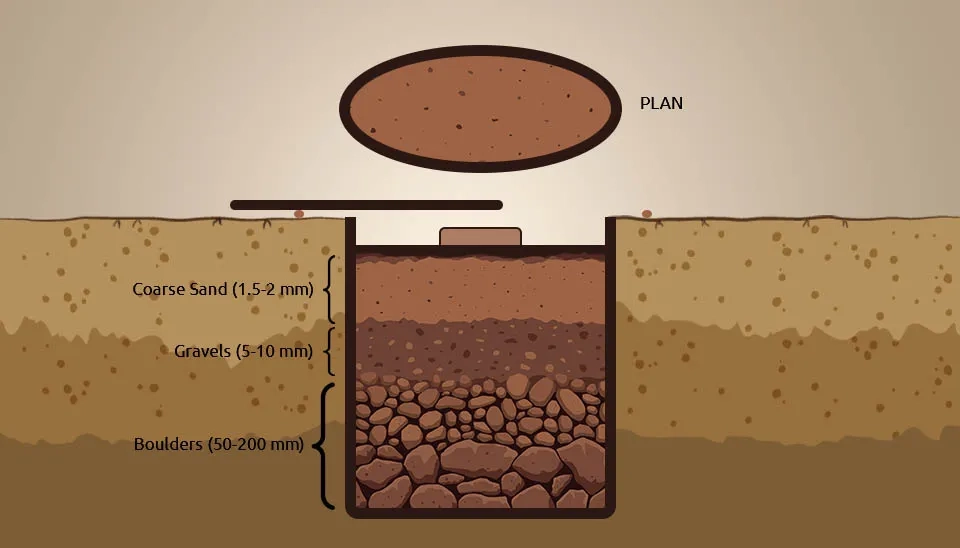

2.1.8. Recharge Pits

Aquifers are not always hydraulically connected to surface water. On a regional scale, impermeable layers or lenses form a barrier between the surface water and the water table, making water spread methods less effective. For effective recharge of the shallow aquifer, the less permeable horizons have to be penetrated to make it directly accessible. Recharge pits are one option. They are excavations of variable dimensions that are sufficiently deep to penetrate less permeable strata. The larger the cross-sectional area of the pit bottom, the more effective it will be. The actual area required depends on the design recharge volume and the permeability of the underlying strata. Therefore, the permeability has to be determined. The steep side slopes and low permeability of these strata mean that sedimentation occurs only at the bottom and that the clogging of side walls is limited. The bottom area of open pits may require periodic manual cleaning. To achieve that condition, the pits after excavation are filled with gravel, sand, and boulders, which act as a filter medium. Cleaning of the pit area should be done occasionally (Reba et al., 2017).

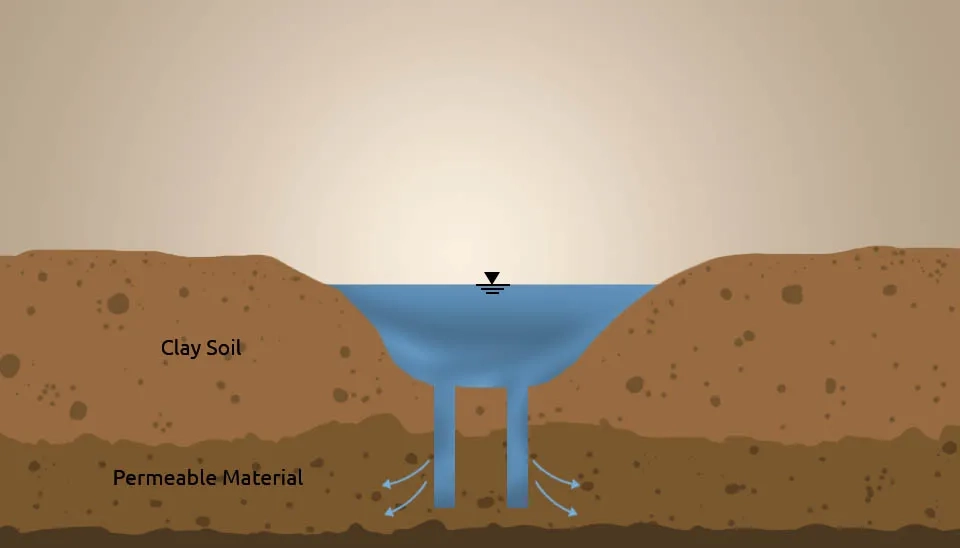

2.1.9. Recharge Shafts

In cases where an aquifer is located deep below the ground surface and overlain by poorly permeable strata, a shaft is used for artificial recharge. A recharge shaft is similar to a recharge pit but much smaller in cross-section. A recharge shaft may be dug or drilled. Pebbles, sand, and boulders fill the recharge shafts, and one can clean them by simply removing the top layers and refilling them. This type of groundwater recharge is most commonly seen in areas where the shallow aquifer is located. They are constructed where there is low permeability and end in a more permeable layer. Usually, the depth of the recharge shaft varies from 10 to 15 m below the ground level (Raicy and Elango, 2020).

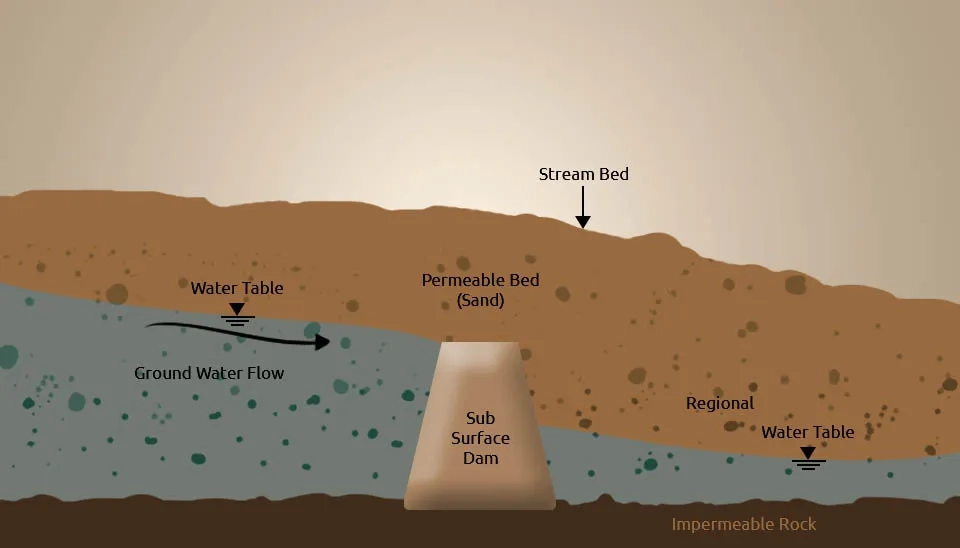

2.1.10. Subsurface Dams

A subsurface dam is a facility that stores groundwater in the pores of the strata to enable its sustainable use. Subsurface dams are barriers of low permeability that are constructed underground. These structures reduce or stop the lateral flow of groundwater to store water below ground and elevate the groundwater table. To construct subsurface dams, a trench is built across a stream or valley until the depth of the bedrock or a layer of clay is reached. Within the trench, an impervious or low-permeability wall is constructed and the trench is afterward filled with the excavated material. The main cause of groundwater dams is to capture the flow of groundwater out of the sub-basin and increase the storage capacity of the aquifer (Lalehzari and Tabatabaei, 2015).

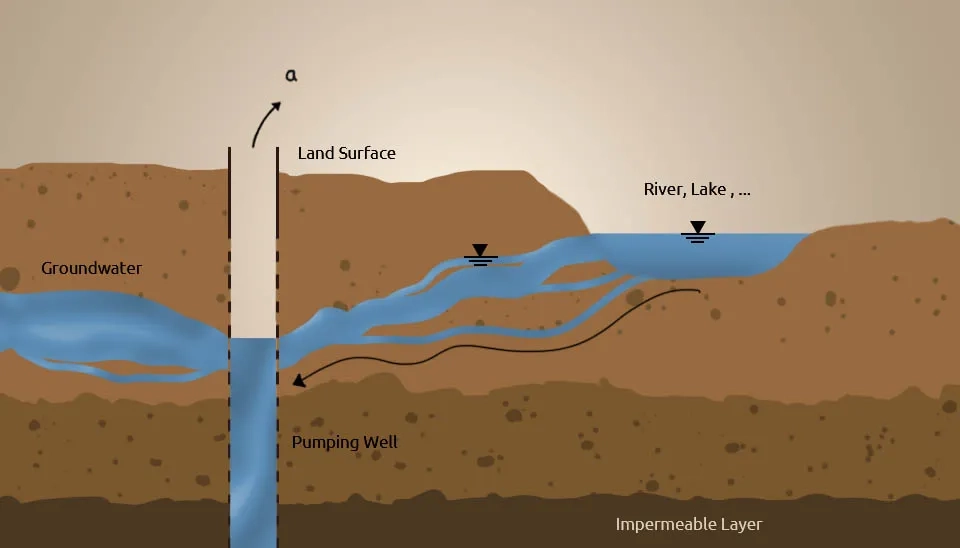

2.2. Indirect Method

The indirect method of artificial feeding is pumping from an aquifer that has a hydraulic connection with surface water sources; recharge is induced through this connection. When the cone of depression intercepts the river recharge boundary, a hydraulic connection gets established with a surface source, which starts providing part of the pumpage yield. In these methods, there is no artificial increase in groundwater storage; instead, surface water simply passes through an aquifer to reach the pump. In this sense, it is more a pumpage augmentation than an artificial recharge measure. Usually, groundwater recharge methods are effectively implemented, as the abandoned channels in the hard rock regions act as a good site for the induced process of recharging. For this process, the check weir at the stream channel helps in the infiltration of water from surface reservoirs to the abandoned channels, which are then directed towards the aquifers.

During unfavorable hydrogeological conditions, the induced recharge process has a greater advantage and it also helps improve the quality of surface water, which is generally better due to its path through the aquifer material before it is discharged from the surface. Additionally, people construct collector wells to obtain extremely high water supplies from riverbed deposits or waterlogged areas. If the phreatic aquifer is situated near a river of limited thickness, then instead of horizontal wells, vertical wells could be adopted, which are more effective than the others.

In this method, the construction of small drains along contours of hilly areas is done so that the runoff in these drains is collected in a cistern, which is located at the bottom of a hill or a mountain. This water is used for irrigation or drinking purposes, and the quality is excellent (Cuthbert et al., 2016).

3. Conclusion

Groundwater recharge approaches include recharge as a natural part of the hydrologic cycle and human-induced recharge, either directly through spreading basins or injection wells or because of human activities such as irrigation and waste disposal. Artificial recharge with excess surface water or reclaimed wastewater is increasing in many areas, thus becoming a more important component of the hydrologic cycle. Typically, most water from precipitation that infiltrates is not used for recharge. Instead, it is stored in the soil zone and eventually returned to the atmosphere by evaporation and plant transpiration. The percentage of precipitation that becomes diffuse recharge is highly variable, being influenced by factors such as weather patterns, properties of surface soils, vegetation, local topography, depth to the water table, and the time and space scales over which calculations are made. Recharge to the water table can occur in response to individual precipitation events in regions having shallow water tables. The need to proceed from a well-defined conceptualization of different recharge processes must be emphasized. The choice of technique must also be guided by the objective of the study, hydrogeological conditions, the available ground space, the water need, the composition of the infiltrated water, the degree of purification, available data, the possibility to get supplementary data, and, of course, financial means.