Have you ever pondered the existence of a revolutionary synergy that has the potential to revolutionize the field of heavy metal removal from wastewater? Among its various applications, the microalgal-bacterial consortium for heavy metals removal has shown exceptional uptake and biotransformation capacity.

Recent progress in urbanization and industrialization has made the increasing pollution of water systems with Heavy Metals (HM) a pressing issue. Various HMs like cadmium (Cd), manganese (Mn), nickel (Ni), copper (Cu), cobalt (Co), silver (Ag), chromium (Cr), and lead (Pb) are generated in different industries such as leather/tanning, electroplating, steel, textiles, and storage batteries (Khan et al., 2023). Water contamination produces enormous problems, including water shortages for drinking, groundwater, lakes, and ocean quality; the fauna and flora of the ecosystem; and operational challenges in industries and households. (Jiang et al., 2020). HMs have been observed in various fishes (in the gills, muscles, and liver tissue sections) of contaminated marine ecosystems and excessive cadmium in rice, and they can accumulate in multiple organs of the human (or even children’s blood) body when they enter the food chain (Uddin et al., 2020; Briffa et al., 2020). HMs react with organisms’ components, such as inorganic carbonate and phosphate, to form inorganic metal salts (proteins, fatty acids, or amino acids) and organic acid salts and chelates, which will cause human physiological health problems (Rashid et al., 2023). So, heavy metals removal by the microalgal-bacterial consortium has developed as a primary study issue within the domain of environmental protection.

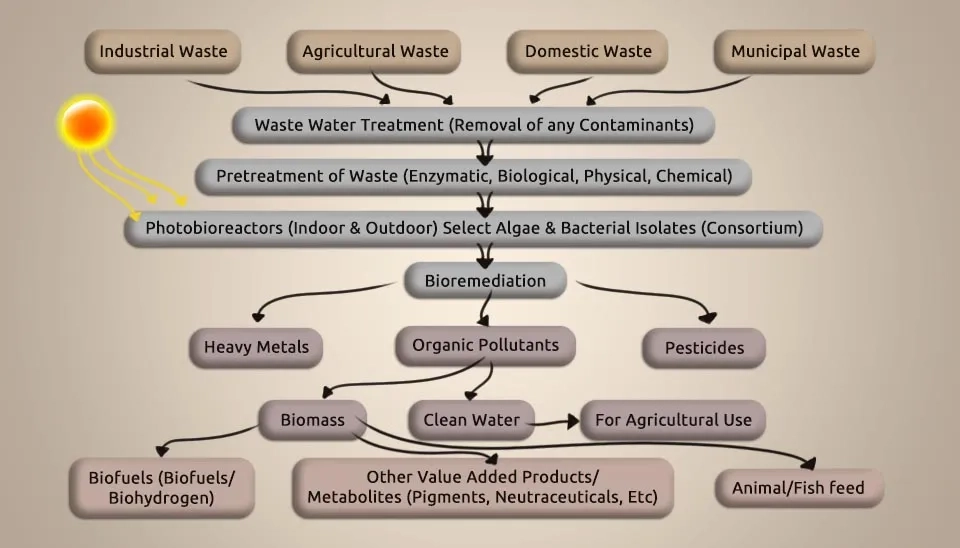

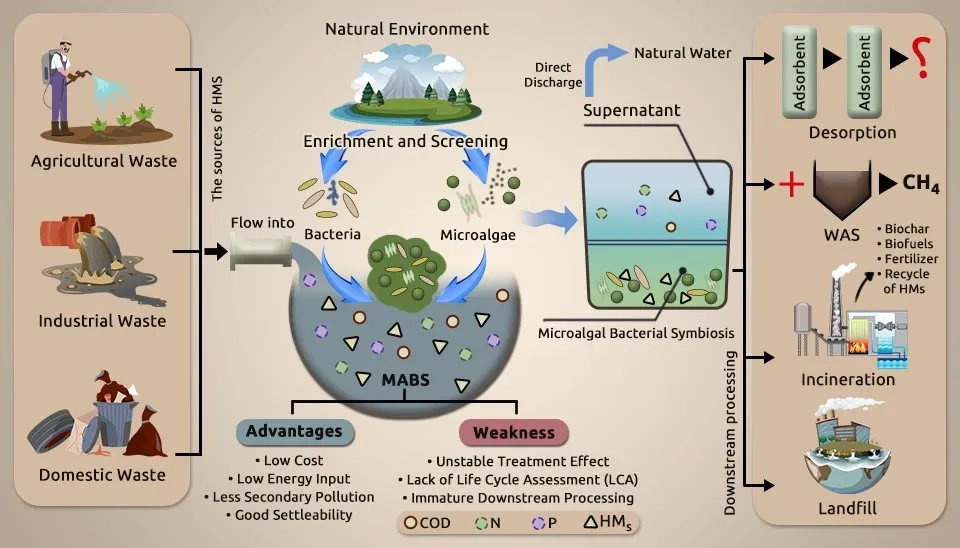

Recently, wastewater treatment has focused a lot of attention on these groups of microalgae and bacteria, particularly their biosorption and biodegradation tools. They have gotten a lot of attention because they can remove inorganic pollutants. Bacteria existing in aquatic environments have an incredible propensity to co-occur in bioremediation. This article discusses recent research on heavy metal removal in wastewater using Microalgae-Bacteria Consortium (MBC). Table 1 provides a summary of this research. The co-cultivation of a microalgae-bacteria consortium, a sustainable process, is towards the production of biomass feedstock coupled with wastewater treatment. Sustainability is to be achieved via the symbiotic growth of microalgae and bacteria, coupled with the use of wastewater as a cheap source of nutrients and water.

Table 1. Performance of metal removal from wastewater using microalgae and bacterial species

Microalgae species | Bacteria species | Metals removal | Metals |

Cladophora glomerata | Bacillus pakistanensis | 46.1 | Mn |

Cladophora glomerata | Bacillus pakistanensis, and Lysinibacillus composti | 38.4 | Mn |

Download Full Table of Performance of metal removal from wastewater using microalgae and bacterial species

1. Mechanisms of Microalgae-Bacteria Consortium in Wastewater Remediation

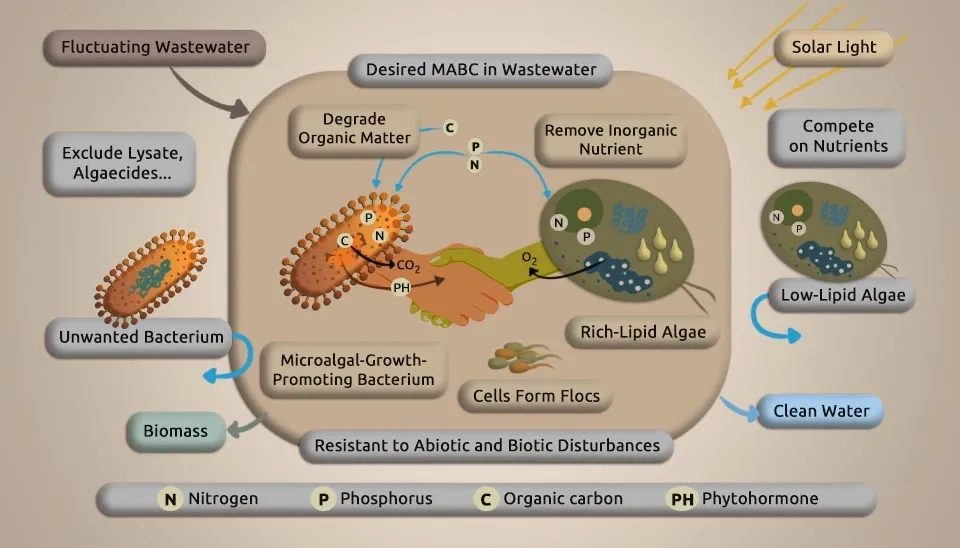

MBC has advantageous and valuable properties. Microalgae take up carbon dioxide by photosynthesis, changing inorganics into organic ones while discharging oxygen. Oxygen-consuming bacteria devour both oxygen and organics, releasing carbon dioxide. Both depend on one another to attain advantageous interactions to form a consortium. Microalgae and bacteria are characterized by their small size, large specific surface area, overwhelming growth and metabolism, high regenerative capacity, high biological activity, high adsorption capacity, environmental versatility, omnipresence in the water environment, inexpensiveness, and simple accessibility. Therefore, these characteristics make them highly valuable as biosorbents. Their use is particularly exceptional in treating wastewater with a low concentration of heavy metals (HMs) and a large amount of sewage. Using heavy metal removal by a microalgal-bacterial consortium for wastewater treatment has the advantages of a high removal rate, higher metabolic efficiency, a fast reaction rate, higher adsorption capacity for substances, easy reproduction, no secondary pollution, selective removal of heavy metals in wastewater using the microalgal-bacterial consortium method, and the treatment works very well, recovering a few HMs with only small investments and low running costs. The microalgal-bacterial consortium in wastewater treatment to remove heavy metals (HMs) involves a complex interaction among microalgae, bacteria, and the physical and chemical environment. Understanding the mechanism of heavy metal removal by a microalgal-bacterial consortium and optimizing the method can be challenging (Fallahi et al., 2021). The microalgae-bacteria consortium system demonstrates consistently high efficiency in removing heavy metals from wastewater.

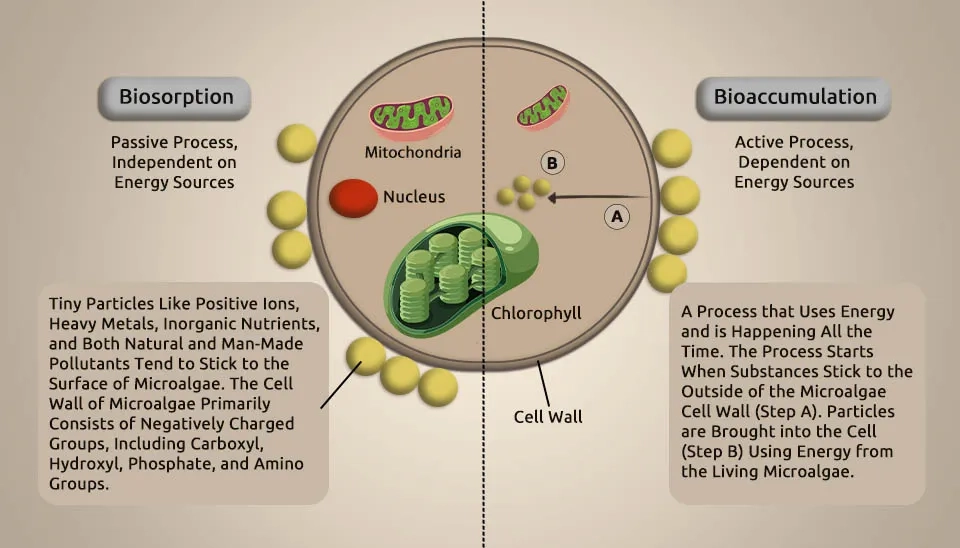

The metal accumulation mechanisms primarily incorporate adsorption on the cell surface and absorption into the cell. Both biosorption and bioaccumulation processes depend on official chelation with different beneficial strains in and out of cells. Bacteria may improve the resilience and removal of HMs by microalgae. For example, at pH 5.7, axenic Chlorella was more sensitive to Cu than algal cells with bacteria; the IC50 values for Cu were 46 and 208 μg L-1, respectively, after 72 hours of treatment (Levy et al., 2009). The microalgal-bacterial consortium for wastewater treatment increased the tolerance of microalgae to mercury (Hg) and cadmium (Cd). In addition, a symbiont of microalgae and bacteria removed more than the number of HMs compared to microalgae or bacteria alone. The way MBC works with HMs might be that the combination of microalgae and bacteria helps produce more EPS, which improves their ability to attract HMs, making HMs less available and harmful in water, and allowing microalgal-bacterial groups to better treat wastewater and reduce HM pollution (Tang et al., 2018). Additionally, bacteria can improve their tolerance to HMs by regulating the Quorum Sensing (QS) system. Bacteria stimulated their LuxI/LuxR and TraI/TraR QS systems under HM exposure to enhance communication and decrease HM absorption. Notably, wastewater heavy metal elimination is rarely explored in MBC stems, with most studies focusing on microalgae and bacterial systems. Higher levels of HMs can alter the microbial community and reduce its ability to remove COD (Mahmoud et al., 2021). Biosorption is a natural process that doesn't need energy. In this process, harmful substances such as heavy metals and organic compounds adhere to the outer surface of microalgae cells due to specific charged components on the cell wall. Bioaccumulation is a process that utilizes energy to facilitate the movement of pollutants from the outside of a cell into the cell itself, where they can be stored or rendered less harmful (Long et al., 2024).

2. Introducing 15 Varieties of Microalgal-Bacterial Systems for Efficient Heavy Metals Removal

Urbanization and industrialization could make aquatic contamination a pressing issue. Industrial wastewater contains pollutants that pose an incredible threat to the environment and humans and could be an enormous challenge for industries. The source of microalgae and bacterial species is comprehensive and can be gotten and screened nearly from any carrier material, particularly from regions contaminated with HMs. The microalgal-bacterial consortium for wastewater treatment is among the most promising technologies for heavy metals removal because of its high efficiency and maintainability. Therefore, this article discusses the current conventional treatment that MBC uses. In the following, the types of microalgae and bacteria that can remove HMs have been introduced, and the test conditions have been described. This review is anticipated to bring noteworthiness to industrial partners, including engineers, environmental technologists, and business entities, in creating and contributing more viable ways of heavy metal removal by the microalgal-bacterial consortium for overall environmental maintainability.

2.1. Microalgae— Cladophora glomerata; Bacteria— Bacillus pakistanensis, and Lysinibacillus composti

Bashir et al. (2023) investigated bioremediation in wastewater (metal-polluted industrial) with algal-bacterial consortia. The bacterial species Lysinibacillus composti (G-positive) and Bacillus pakistanensis (G-positive) were the microalgal species Cladophora glomerata. The bacteria and microalgae were cultured in the Industrial wastewater (IWW) of Hayatabad Industrial Estate (HIE) for 14 days in light and dark conditions at 14:10 h and room temperature. The rationale behind determining these microalgae and bacterial species is their rapid development at high and low temperatures. The WW of HIE contains organic and inorganic pollutants from the paper industry, matches, incinerators, pharmaceuticals, plastics, steel, paint, and rubber. Metals like Mg, Ca, Ag, Cd, Cr, Co, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Mn were in IWW. To investigate the efficiency of the MBC for pollutants, six pots were thoroughly washed with distilled water and diluted with nitric acid. Three banks served as controls, receiving tap water, while three treatment pots received IE. The experimental pots marked E1, E2, and E3 each had 500 ml of IE for Bacillus pakistanensis-Cladophora glomerata, Lysinibacillus composti-Cladophora glomerata, and Bacillus pakistanensis-Lysinibacillus composti-Cladophora glomerata. Also, the pots labeled CT1, CT2, and CT3 were controlled with 500 ml of tap water. After treatment, significant diminishments were gotten within the following parameters and percentages: color 85.7%, Electrical Conductivity (EC) 40.8%, turbidity 69.6%, sulfide 78.5%, fluoride 38.8%, chloride 62.9%, Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) 66%, Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) 81.8%, Total Suspended Solids (TSSs) 82.7%, Total Dissolved Solids (TDSs) 24.6%, Ca hardness 37.2%, Mg hardness 50%, and total hardness 39%. The selected species removed 98.2% of Mn, 94% of Cu, 97.7% of Cr, 91.6% of Cd, 92.8% of Co, 79.6% of Ag, 82.6% of Ni, 98% of Ca, 90% of Mg, and 82.1% of Pb. The Bioconcentration Factor (BCF) values shown by the consortia for Mn, Cu, Cr, Cd, Co, Ag, Ni, Ca, Mg, and Pb were 91.8%, 67%, 97.5%, 83.3%, 85.7%, 48.1%, 80.4%, 84.3%, 82.5%, and 80.3%, respectively. The t-test showed that the treatment with the chosen species greatly lowered the amount of HM in the IWW, which was caused by the group of algae and bacteria (p ≤ 0.05) (Bashir et al., 2023).

2.2. Microalgae— Chlorella sp., Scenedesmus obliquus, Stichococcus, and Phormidium sp.; Bacteria— Pseudomonas putida, Burkholderia sp., alkanotrophic bacteria, Kibdelosporangium aridum, Acinetobacter oleovorum, and Bacillus sp.

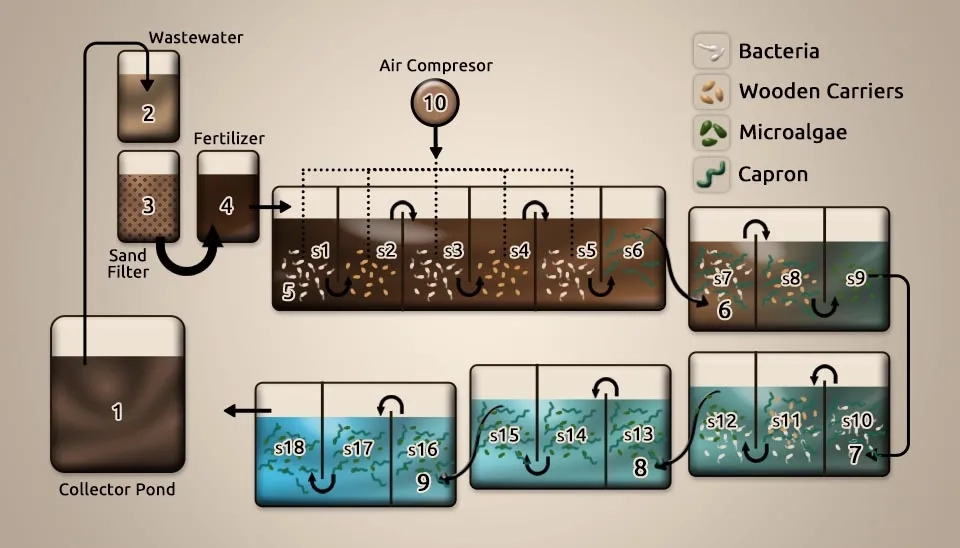

Safonova et al. (2004) investigated the biotreatment of industrial wastewater by selected algal-bacterial consortia within a volume of 120,000 m3. It occupies 30,000 m³ of industrial wastewater from a pond in Samara, Russia. Wastewater characteristics of COD25, BOD25, NH4+, Cu, Ni, Cd, Al, Cr, Mn, phenols, anionic Surface-Active Substances (SAS), and oil spills (mg L-1) were 1,200, 664, 1.1, 0.035, 0.021, 0.004, 0.04, 0.12, 0.19, 0.48, 22.25, and 40, respectively. Bacterial strains like Pseudomonas putida, Burkholderia sp., Kibdelosporangium aridum, Acinetobacter oleovorum, and Bacillus sp., along with microalgae strains such as Chlorella sp., Scenedesmus obliquus, some Stichococcus strains, and Phormidium sp., were identified. After screening microalgae and bacteria for resistance to the wastewater, the following strains were selected: the algal strains Chlorella, Scenedesmus obliquus, a few Stichococcus strains, and Phormidium sp., and the bacterial strains Rhodococcus and Kibdelosporangium aridum, as well as two unidentified bacterial strains isolated from the collector lake. The figure showed collector pond; 2: tankA with wastewater; 3: tankB with sand filter (2/3 part of the tank); 4: tankC with the fertilizer; 5: reservoir No. 1 with bacteria immobilized on ceramics (sections: s1, s3, s5), capron (section: s6) and wooden (sections: s2, s4) carriers; 6: reservoir No. 2 with bacteria immobilized on ceramics (section: s7), capron (sections: s7, s8), wooden (section: s8) carriers and algae immobilized on capron fibers and nets (section: s9); 7: reservoir No. 3 with bacteria immobilized on ceramics (sec- tion: s10), capron (sections: s10, s11), wooden (unit: s11) carriers and algae immobilized on capron fibers and nets (section: s12); 8: reservoir No. 4 with plants and algae immobilized on capron (sections: s13, s14, s15) carriers; 9: reservoir No. 5 with plants and algae immobilized on capron (sections: s16, s17, s18) carriers; 10: air compressor. All the strains recorded above were immobilized onto different solid pages (capron fibers for microalgae; ceramics, capron, and wood for bacteria) and utilized for biotreatment in a pilot establishment. The results showed that the chosen microalgae and bacteria formed steady consortia during the waste degradation, which was illustrated for the first time for the microalgae Stichococcus. Stichococcus and Phormidium cells connected to Capron filaments, with the assistance of slime, formed a matrix. This matrix settled the bacteria and eukaryotic microalgae and prevented them from being washed off. A critical decrease in the substances in the poisons was observed: phenols were removed up to 85%, anionic SAS up to 73%, oil spills up to 96%, copper up to 62%, nickel up to 62%, zinc up to 90%, manganese up to 70%, and iron up to 64 %. BOD25 and COD reductions amounted to 97% and 51%, respectively (Safonova et al., 2004).

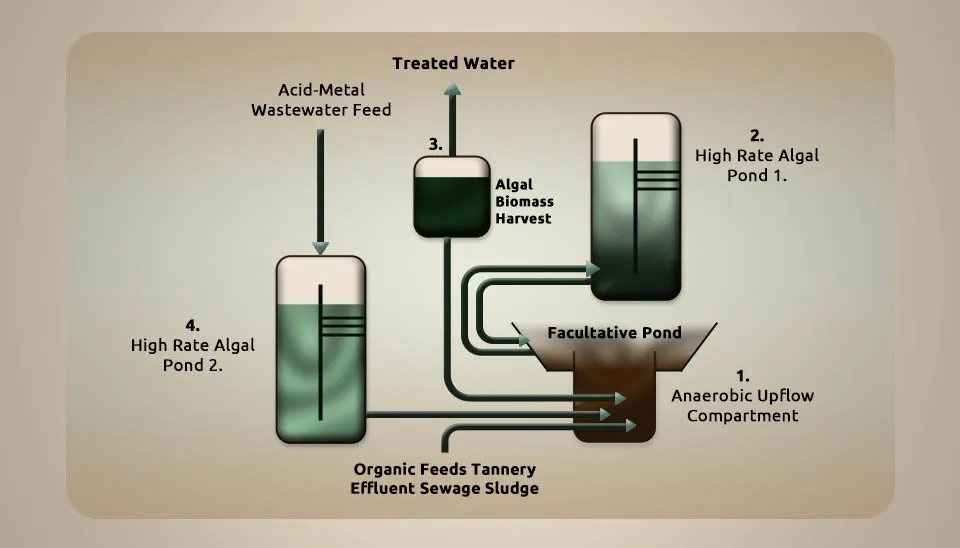

2.3. Microalgae— Spirulina sp.; Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria

Rose et al. (1998) investigated an integrated algal sulfate-reducing high-rate ponding process for treating acid mine drainage wastewater. Metal removal was performed in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks. We controlled the metal removal process to prevent unadulterated metal precipitation at the same pH and different metal concentrations. The detailed results highlighted the differences between control and test readings. We allowed a ten-hour settling period for the removal of the metal accelerator. An up-flow anaerobic reactor (8 L) was fed media with the following composition (g L−1): NH4Cl 0.5; K2HPO4 1.0; mgSO4·7H2O 0.2; CaCl2·2H2O sp. was used as the organic substrate. Dried Spirulina was seeded with sludge from a methanogenic reactor that treats crude sewage. The Spirulina sp. culture for the metal authoritative ponders was isolated from a tannery Waste Stabilization Pond (WSP), grown, and kept up in Zarouk’s media at a consistent temperature of 28°C beneath cold white light with an L/D cycle of 18:6 hours. Cells were gathered by filtration through a GF/C filter or a nylon mesh with a pore size of 50 microns. Metal content in Spirulina was measured in a culture collected and resuspended in either Zarouk’s media or water. The cultures were set on a shaker at 60 rpm, and shifting concentrations of metals were included. Tests were removed at intervals and filtered through a 0.45-micron nylon membrane filter. The use of sulfate-reducing bacteria has been shown to help in treating acid mine drainage, but factors like the need for reactor estimates, costs, and the availability of carbon and electron donor sources limit how much the process can be improved. Treatment of tannery effluent from custom-designed high-rate microalgae ponding systems, and its use as a carbon source in generating and precipitating metal sulfides, has been demonstrated through pilot studies for full-scale application. The treatment of both mine drainage and zinc refinery wastewater is detailed. A supporting method for using microalgae to create alkalinity and remove heavy metals with the help of a mix of microalgae and bacteria has been used, and a combined process called “Algal Sulfate reducing Ponding process for the treatment of Acidic and Metal wastewaters” (ASPAM) has been described (Rose et al., 1998).

2.4. Microalgae— C. vulgaris-BH1; Bacteria— Exiguobacterium profundum-BH2

Batool et al. (2018) investigated the implication of highly metal-resistant microalgal-bacterial co-cultures for the treatment of simulated metal-loaded wastewater channels flowing through Mohanlal, Lahore, Pakistan. A sterile holder collected the wastewater test from the depleted area under clean conditions. The temperature and pH of the wastewater at the time of testing were noted to be 32.4 °C and 7.3, respectively. Pure samples of microalgae and bacteria that can resist multiple metals (Cu, Cr, and Ni) were collected using the streak-plate method with BG-11 and nutrient agar as growth media. The medium was arranged by blending 10 of the three stock arrangements (1–3), 1 ml of the stock arrangement 4, 0.02 g of Na2CO3, and 1.5 g of NaNO3 in refined water to create 1 L of the arrangement. The nutrient agar composition (g L−1) was beef extract, 3; peptone, 5; agar, 15; and water, 1000 ml. The microalgal and bacterial strains were found to stand up to 100 ppm of the abovementioned HMs freely. However, when employed in mixture form, the microalgal and bacterial strains could resist 120 ppm of metals, breaking even with concentrations (40 ppm) of each of the abovementioned metals. Freshly grown microalgal-bacterial consortiums for wastewater treatment societies were blended to different extents. Five diverse bits of possibly mutualistic microbial co-cultures (comprising microalgal and bacterial cells in proportions of 1:3, 2:3, 3:3, 3:1, and 3:2) were arranged and utilized to remediate misleadingly prepared HM-rich wastewaters. Chlorella vulgaris-BH1 and Exiguobacterium profundum-BH2 species were then co-cultured in five different proportions. At that point, the MBC was autonomously uncovered in the wastewater, which contained 100 ppm of each HM. The show's results showed that approximately 78.7%, 56.4%, and 80% of Cu, Cr, and Ni were removed after a hatching period of 15 days. The metal-binding capacity (MBC) in a ratio of 3:1 indicated the highest remedial potential (Batool et al., 2018).

2.5. Microalgae— Scenedesmus acutus and Chlorella pyrenoidosa; Bacteria— Bacillus sp. and Micrococcus sp.

Chandrashekharaiah et al. (2022) investigated how algae-bacterial aquaculture can enhance heavy metal removal in wastewater (Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺) and water reuse efficiency of synthetic streams in Jamnagar, Gujarat, India. Scenedesmus acutus and Chlorella pyrenoidosa were grown in Fog’s media supplemented with different concentrations of Pb²⁺ (0 (control), 300, 350, 400, 450, 500, 550, and 600 ppm) and Cd²⁺ (0, 1.5, 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, 10.0, 12.5, and 15 ppm) for 96 h. The person jars containing Fog’s media supplemented with 200 ppm Pb²⁺ and 1.5 ppm Cd²⁺ were inoculated (mid-log phase) with 50%:50%, 75%:25%, and 25%:75% proportions of S. acutus and C. pyrenoidosa with a last inoculum concentration of 20%. The exploratory flasks (250 ml media/500 ml flask) with bacteria and bacterial consortia were incubated in an incubator shaker and guaranteed 25±1 °C and 120 rpm disturbance. A shaker held the experimental flasks containing microalgae, bacteria, and a microalgal-bacterial consortium for wastewater treatment. They kept up at 2 LPM CO2 blended air (98% air + 2% CO2), 120 rpm disturbance, 25 ± 1◦C, 12:12 h L/D photoperiod, and 250 µmoles m-2 s−1 light intensity. The culture pH of all the tests was kept at 7.0 ± 0.5. The protocooperation of MBC was considered during the bioremediation in wastewater of Pb2+ and Cd2+, taken after a bioassay thought about with bioremediation in wastewater stream utilizing Sorghum bicolor. The Bacterial (Bacillus sp., Bacillus sp., and Micrococcus sp.) and Microalgae (Scenedesmus acutus and Chlorella pyrenoidosa) consortium was developed in such a way that it can endure and efficiently remove 200 mg L-1 Pb2+ and 1.5 mg L-1 Cd2+. The MBC in the protocooperation study showed ~30–33% higher bioremediation in wastewater than microalgae and bacteria alone. Due to positive protocooperation, 30% higher microalgae Ash Free Dry Weight (AFDW), 13% higher bacterial Colony-Forming Units (CFU) ml−1, 82% lower Dissolved Oxygen (DO), and 62% higher bicarbonates were detailed as compared to individual consortia systems (Chandrashekharaiah et al., 2022).

2.6. Microalgae— Chlorella sorokiniana and Chlorella sp.; Bacteria— Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus

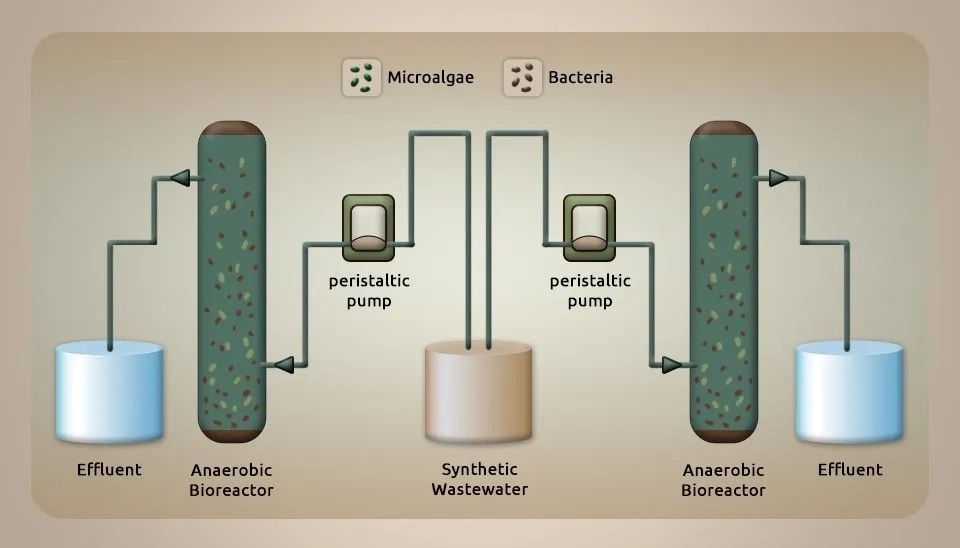

Makut et al. (2019) investigated the production of microbial biomass feedstock via co-cultivation in a microalgal-bacterial consortium coupled with effective wastewater treatment in Guwahati, India. Two microalgal (Chlorella sorokiniana and Chlorella sp.) and two bacterial (Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus) strains were used for MBC. All the tests were carried out in an orbital shaker at 150 rpm and 30 °C under 100 μEm−2 s−1 light intensity with an L/D cycle of 16:8 h using an Artificial WasteWater (AWW) medium for 7 days. The use of a bioreactor with a working volume of 3 L was carried out at 30 °C, an agitator speed of 150 rpm, aeration at 1 vvm, and a light intensity of 250 μEm−2 s−1 for an L/D cycle of 16:8 h. COD, TP, TN, and pH were 1260 mg L−1, 50 mg L−1, 30 mg L−1, and 7.31, respectively. When the consortium was characterized by manufactured wastewater and raw dairy wastewater, a critical advancement in microalgal growth, total biomass titer, COD, and nitrate removal efficiency was observed compared to microalgae alone. Total biomass titer, nitrate removal, and COD removal efficiency were found to be 2.84 g L−1, 93.59%, and 82.27%, and 2.87 g L−1, 84.69%, and 90.49% in artificial wastewater and raw dairy wastewater, respectively (Makut et al., 2019).

2.7. Microalgae— Scenedesmus sp; Bacteria— Activated Sludge

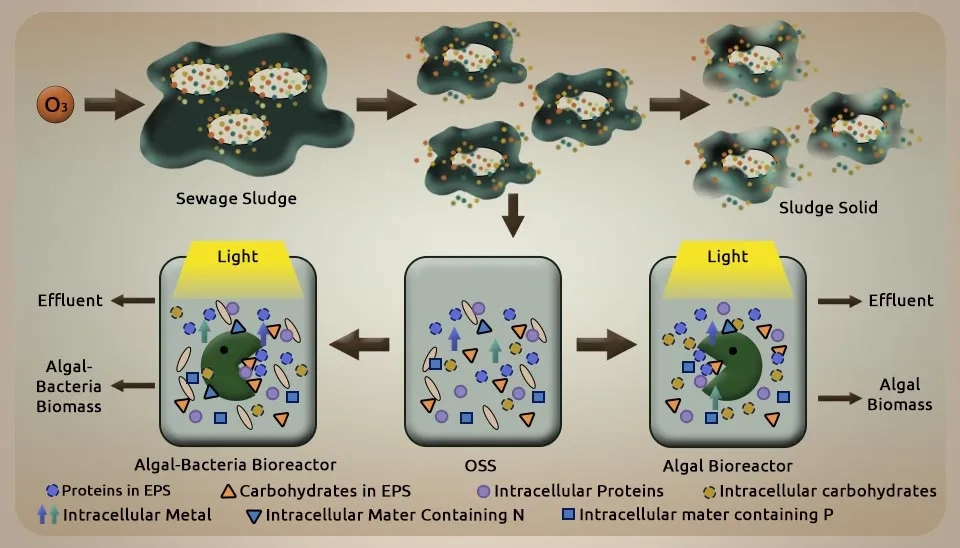

Lei et al. (2018) investigated microalgae cultivation and nutrient removal from sewage sludge from the secondary sedimentation tank of the Taiping Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP) after ozonizing in an algal-bacteria system. The filtered sewage sludge was accelerated for 5 h to thicken the sludge and, after that, put away at 4 ℃ before further utilization (in 48 h). At that point, it is ozonized by an ozonation system that includes an ozonation sludge reactor, an ozone generator, and an abundance of ozone absorption hardware. In brief, 3000 ml of sewage sludge was exchanged into the ozonation reactor and ozonized by 50.4 mg of O3 g-1 SS for 80 minutes, amid which 100 ml of sludge blend was taken out of the reactor every 10 minutes, and another 100 ml of thickened sewage sludge was supplemented into the ozonation sludge reactor at the same time to guarantee the ozonation system running ceaselessly. The ozonized sludge taken from the reactor was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min. After that, the supernatant was utilized for microalgae cultivation, and the residual sludge was exchanged into a membrane bioreactor to encourage treatment. We obtained the microalgae inoculum from the Taiping WWTP's second clarifier divider and cultivated it in BG11 until the microalgae grew exponentially. At that point, the cultivated microalgae were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min, and the dregs were utilized as microalgae (Scenedesmus sp.) inoculum. Meanwhile, the Taiping WWTP's secondary sedimentation tank yielded the AS inoculum. After two weeks of acclimation, the Mixed Liquor Suspended Solids (MLSS) of seed sludge was almost 15,000 mg L-1 as the bacterial inoculum. Three stirred batch photobioreactors (only algae (A), both algae and bacteria with 1:3 (w/w) (AB), and only bacteria (B)) with glass 30 cm in depth and 16 cm in diameter (working volume 5 L) were set up for 10 days. We lit the A and AB systems under the 2500 lx internal divider of the reactors, ensuring a 12:12 L/D cycle per day. The B system was secured with silver paper to prevent the reactor from lighting up. A magnetic mixing bar (80 rpm) was utilized to preserve constant blending and dodge microalgae sedimentation. The results indicated that the growth rate of Scenedesmus sp. in MBC (0.2182) was more significant than within the algae-only system (0.1852). The addition of bacteria improved COD, NH₄⁺-N, TN, and TP removal rates by 23.9 ± 3.3%, 27.7 ± 3.6%, 16.6 ± 1.8%, and 14.9 ± 2.2%, respectively. Also, the microalgal-bacterial consortium for wastewater treatment improved TN and TP removal rates by 32.8 ± 0.7% and 50.3 ± 1.8% from Ozonated Sludge-Supernatant (OSS). The MBC also demonstrated advantages in biomass settleability and HM removal. OSS contained various HMs, such as Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, Zn, etc. During the experiment, the AB system had the best removal efficiencies of all metals, with an order of AB > B > A (Lei et al., 2018) .

2.8. Microalgae— Chlorella vulgaris; Bacteria— phyla Proteobacteria, Synergistetes, and Firmicutes

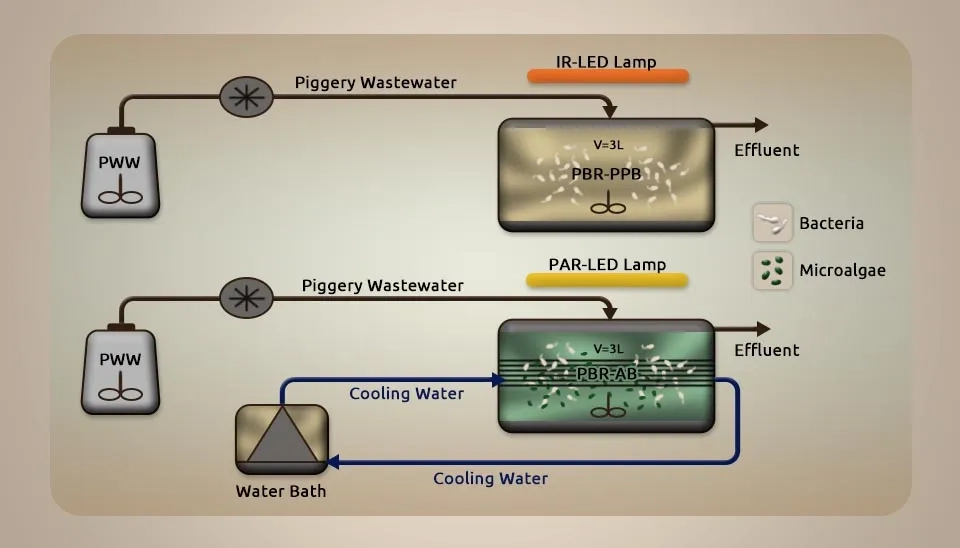

García et al. (2019) systematically compared the potential of microalgal-bacterial and purple phototrophic bacteria consortia for the treatment of piggery wastewater. A Chlorella vulgaris culture obtained from an open-air High-Rate Algal Pond (HRAP) treating center was utilized as an inoculum within the MBC photobioreactor. The PPB inoculum utilized was obtained from a batch improvement in diluted Piggery WasteWater (PWW) collected from a nearby swine farm at Cantalejo (Spain) at 17% beneath continuous InFrared (IR) light intensity at 50 Wm-2. The PWW was centrifuged for 10 minutes at 10,000 rpm before dilution to reduce the concentration of TSS. A microalgal-bacterial consortium for wastewater treatment batch test was conducted in three gas-tight glass bottles of 1.1 L illuminated by Light-Emitting Diode (LED) lamps at 1,380 ± 24 µmol m-2s-1 for 12 h a day. A Purple Phototrophic Bacteria (PPB) batch sample was carried out in 1.1 L gas-tight glass bottles enlightened by IR lamps at 45 ± 1 W m-2 for 12 h per day. Both light intensities were chosen to reenact the natural sun radiation conditions of Photosynthetic Active Radiation (PAR) and IR. The bottles were filled with 400 ml of 5, 10, and 15% diluted PWW and immunized with new biomass at 760 mg TSS/L. Microalgae strains such as Chlamydomonas sp., Chlorella kasseri, Chlorella vulgaris, and Scenedesmus acutus represented 8, 25, 46, and 21% of the microalgae population obtained from the Algal-Bacterial Photobioreactor (PBR-AB). Also, Bacteria from the phyla Proteobacteria, Synergistetes, and Firmicutes represented 83.8, 5.3, and 3.6% of the bacterial population obtained from the PPB photobioreactor (PBR-PPB). All bottles were washed with N2 for 10 min to establish an initial environment utterly free of O2. The samples were incubated at 30°C under continuous magnetic stirring (200 rpm). With a Hydraulic Retention Time (HRT) of 10.6 days, PBR-AB provided the highest efficiencies of nitrogen, phosphorus, and zinc removal (87 ± 2, 91 ± 3, and 98 ± 1%), while PBR-PPB had the highest adsorption capacity. The highest organic carbon removals were obtained at 87 ± 4%. Reducing the HRT from 10.6 to 7.6 and 4.1 days gradually decreased the organic carbon and nitrogen removal but did not affect the removal of phosphorus and Zn in both photobioreactors. The drop in HRT caused a lot of microalgae to be washed out in PBR-AB and greatly influenced the types of bacteria in both photobioreactors (García et al., 2019).

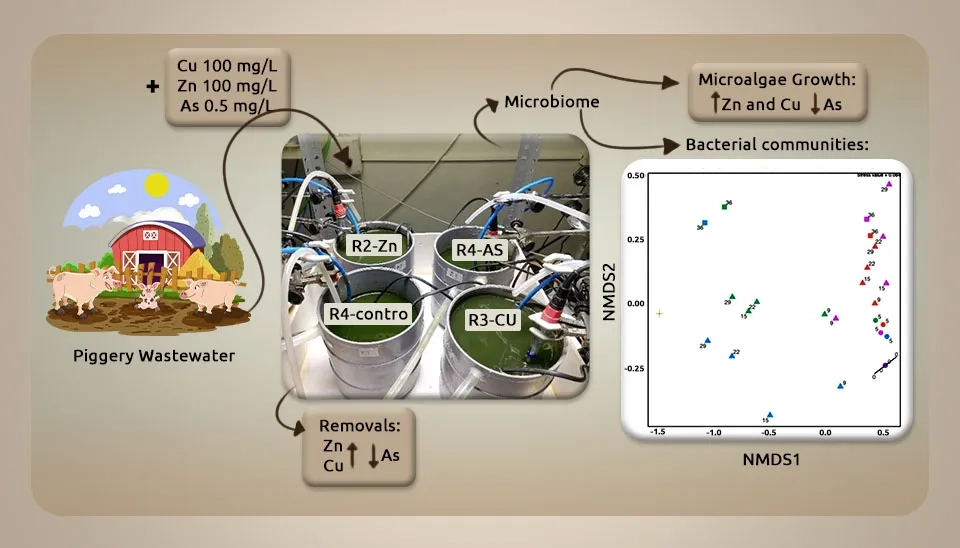

Collao et al. (2022) investigated how current concentrations of Zn, Cu, and As in piggery wastewater compromise nutrient removals in microalgae–bacteria photobioreactors due to altered microbial communities. Two bunches of crude PWW were collected sometime recently at the beginning of each test (A and B) from a farm in Segovia (Spain) at diverse times and put at 4 ℃ until the conclusion of the trial. We centrifuged the crude PWW at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes, and then diluted the supernatant at 5% v/v with tap water. This weakened wastewater was utilized as the reactor feed. To obtain the impact of HMs and As on the execution of the PBRs, two sets of tests (A and B) were performed autonomously for both arrangements of tests. Four open PBRs (R1, R2, R3, and R4) with a capacity of 3 L (16 cm depth) each were utilized. The PBRs were operated under indoor conditions and illuminated at 1400 µmol m-2.s-1 by LED lamps, applying L/D cycles of 12:12 h:h, and the room temperature was 28 to 33 ℃. When the values of the nutrient concentrations within the effluent and the microalgae grew consistent over time, i.e., steady phase, the microalgae–bacteria PBRs were blended to begin the tests with homogeneous microbiomes. The tests were isolated in three stages. First, the four PBRs were improved with 5% PWW for 7 days after achieving a consistent state and blending cultures (stage I). At that point, from day 7 to day 29, R2, R3, and R4 were nourished with PWW weakened at 5% and doped with 100 mg/L of Zn, 100 mg/L of Cu, and 500 µg/L of As, respectively (stage II). From day 29 to day 36, the four PBRs were once more nourished, with PWW weakened at 5% without the expansion of Zn, Cu, or As (stage III). The feed of R1, which was utilized as a control, was not doped with Zn, Cu, or As in any step of the tests. After measurement with Zn (100 mg/L), Cu (100 mg/L), and As (500 µg/L), the high biomass take-up of Zn (69–81%) and Cu (81–83%) diminished the carbon removal within the photobioreactors, repressed the growth of Chlorella sp., and influenced heterotrophic bacterial populations. The biomass take-up result was low (19%) and advanced microalgae growth. The nearness of Cu and As diminished nitrogen removal, lessening the wealth of denitrifying bacterial populations. The results showed that metals influenced 24 bacterial genera, which they did not recoup after introduction (Collao et al., 2022).

2.10. Microalgae— C. vulgaris; Bacteria— Enterobacter sp.

Mubashar and others (2020) studied how Chlorella vulgaris and Enterobacter sp. can remove color and heavy metals from textile wastewater when used together. Freshwater green microalgae strain C. vulgaris was pre-cultured in BG-11 media. The bacterium was cultured in tryptic soy broth (TSB) media with pre-sterilization in an autoclave for 20 min at 121 ℃, sometimes recently utilized for microalgae and bacteria cultivation. Chlorella vulgaris was first grown in small flasks with a light intensity of 60–80 µmol m−2 s−1 and a temperature of 28 ± 2 ℃, then transferred to laboratory-grade plastic tubes (5 L) for 7 days. The culture was then used to help microalgae grow in textile wastewater. The bacteria were grown in 500 ml Erlenmeyer flasks in a shaking incubator at 150 rpm for 48 h at 25 ± 2 ℃. Three wastewaters were made by adding different dilutions (5%, 10%, and 20%) to make them less toxic. The pH of all the dilutions was set to 7.0 before inoculating algal–bacterial strains to assess the wastewater treatment potential of microalgae, respecting controls of the same dilutions. The microalgal strain C. vulgaris was developed in all these weakenings of wastewater for biomass generation. Pre-cultured microalgae were centrifuged at 3700 g at 20 ℃ for 5 min. After the supernatant was disposed of, the microalgal cells were washed twice with sterile refined water, and an OD of 0.2 was set employing a spectrophotometer at 750 nm absorbance. Indoor culture conditions were maintained in a growth chamber with a temperature of 25 ± 1 ℃ and 14:10 h L/D cycle at the intensity of 100–120 µmol m−2 s−1 given with cool white fluorescent lamps. The higher Chlorella to Enterobacter proportion was chosen because a bacterial population does not result in an uncontrolled culture, and excellent efficiency and microalgal-bacterial consortium for heavy metals removal should be kept up under a higher microalgae population. Enterobacter sp. found the Most outstanding results at a 5% weakening level. MN17-inoculated C. vulgaris medium, as Cr, Cd, Cu, and Pb concentrations were decreased by 79%, 93%, 72%, and 79%, respectively. The values of COD and color were also significantly reduced by 74% and 70%, respectively, by MBC. The present investigation uncovered that the microalgal-bacterial consortium for wastewater treatment enhanced the removal of coloring agents and HMs from textile wastewater by invigorating algal biomass growth (Mubashar et al., 2020).

2.11. Microalgae— Scenedesmus sp., Tetraerdon sp., Chlorella sp., and Chlorococcus sp.; and Bacteria— Chroococcus sp., Pseudoanabaena sp., and Leptolyngbya sp.

Loutseti et al. (2009) investigated the application of a microalgal-bacterial biofilter to detoxify copper and cadmium metal wastes. The biomass was delivered in an artificial stream utilizing the effluent of a municipal WWTP as a nutrient source, with the additional benefit of reducing phosphorus and nitrogen loadings. Microalgal-bacterial biomass from the secondary treatment stage of the WWTP (Greece) was used for the batch biosorption tests. The biomass was dried at 65 °C until steady weight, after sun-drying and autoclave sterilization after careful washing with deionized water, and then dried at 65°C. Biosorption effectiveness was surveyed by permitting the MBC to contact 10 and 1000 mg/L arrangements of each metal (Cd2+ and Cu2+) for 1, 5, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min. Separate tests with dH2O-treated biomass were also performed at pH 4.0 for 15 minutes of ceaseless stirring to test the impact of various introductory metal concentrations (10, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, and 1000 mg/L). In all batch tests, the biomass was removed earlier to investigate by centrifugation from all tests, and 5 ml of the supernatant was collected and put away in little plastic containers at 4 °C with the addition of a 0.1 ml 65% HNO3 solution. Optimum adsorption for Cd2+ and Cu2+ was achieved by 80–100% with the deionized-H2O conditioned biomass at an initial pH of 4.0. Results showed a high affinity of the used biomass for Cd2+ and Cu2+ at Qmax 18–31 mg metal/g.d.w. in the Langmuir model. During tests, it was found that HM removal using Ca-alginate or biomass beads is affected by how fast the liquid flows and how much waste is treated. Removing both metals using weak acids was very successful, 95–100% (Loutseti et al., 2009).

2.12. Microalgae— C. sorokiniana; Bacteria— R. basilensis

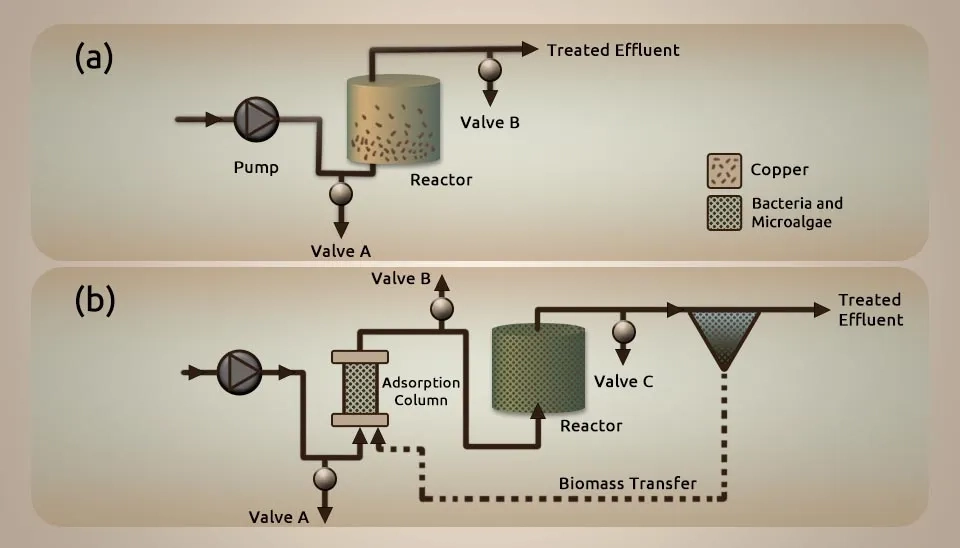

Mun˜oz et al. (2006) investigated the sequential removal of heavy metal ions and organic pollutants using an algal-bacterial consortium. The remaining MBC biomass from photosynthetically bolstered organic pollutant biodegradation processes in encased PBR was tried for its capacity to accumulate Cu(II), Ni(II), Cd(II), and Zn(II). Salicylate was chosen as a demonstrated contaminant. The MBC biomass combines microalgae's high adsorption capacity with the leftover biomass's low cost, making it an alluring biosorbent for natural applications. A Mineral Salt Medium (MSM) was used for the cultivation of C. sorokiniana employed for the adsorption experiments in 155ml glass flasks with a working volume of 50 ml and a mixture of CO2/N2 (30/70% v/v) as gas headspace. Also, R. basilensis was cultivated in 1 L conical flasks with 500 ml of sterile MSM containing sodium salicylate at 2 g L-1 and inoculated with R. basilensis at 1% (v/v). All the tests were then done and incubated in an incubator shaker at 150 rpm beneath light intensity at 100 µmol m−2 s−1 at 26 °C for one week. The biomass was collected by centrifugation at 18.000 · g for 20 min, washed three times with a 0.9% NaCl arrangement to evacuate the remaining salts and EDTA, and resuspended in a 0.9% NaCl solution.

Cu(II) was especially taken up from the medium when the metals were displayed independently and in combination. There was no competition for adsorption locales, which proposed that Cu(II), Ni(II), Cd(II), and Zn(II) tie to distinctive locales in which dynamic Ni(II), Cd(II), and Zn(II) authoritative bunches were shown at deficient concentrations. Therefore, we gave Cu(II) biosorption an exceptional center. Cu(II) biosorption by the MBC biomass was characterized by a starting quick cell surface adsorption followed by a slower metabolically driven uptake. pH, Cu(II), and algal-bacterial concentration essentially influenced the biosorption capacity for Cu(II). Maximum Cu(II) adsorption capacities of 8.5 ± 0.4 mg g⁻¹ were accomplished at a beginning Cu(II) concentration of 20 mg L1 and pH 5 for the tested MBC biomass. These are reliable, with values detailed for other microbial sorbents under comparative conditions. Cu(II) desorption from soaked biomass was attainable by elution with a 0.0125 M HCl arrangement. Concurrent Cu(II) and salicylate removal in a continuously stirred tank PBR were not doable due to the high toxicity of Cu(II) towards the microbial culture. Using an adsorption column filled with a mix of microalgae and bacteria for wastewater treatment before the PBR lowered the Cu(II) levels, allowing the PBR to break down salicylate afterwards (Mun˜oz et al., 2006).

2.13. Microalgae— Chlorella vulgaris, Scenedesmus obliquus, Selena's-Trump Capricornutum, and Anabaena spiroides; Anaerobic Fermentative Bacteria

Li et al. (2018) studied how to clean up Cu(II)-polluted wastewater using beads made of sulfate-reducing bacteria and microalgae in a system that treats the water continuously and looks at how it works. Microalgae were picked as a food source for sulfate-reducing bacteria because they break down more quickly than other materials. They made beads with bacteria and microalgae that couldn’t move. Then, they used them to clean up fake Cu(II) water. Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria (SRB) cultures were taken from the anaerobic sludge of a cow farm in China. Microalgae and bacteria were grown in closed glass bottles containing modified Postgate B at 30 °C for 7 days. Microalgae such as Chlorella vulgaris, Scenedesmus obliquus, Selenas-Trumcapricornutum, and Anabaena spiroides were cultivated in 1000 ml flasks filled with BG11 medium. Microalgae were centrifuged at 5000 rpm to remove extraneous materials and salts for 20 min and sterilized in an autoclave at 121 °C for 20 min before being used as a carbon source for SRB. Also, they looked at how microalgae ferment without oxygen and placed a specific number of inactive microalgae into 500 ml bottles containing 10 ml of soil supernatant. These were then shaken and cultured at 30 °C. They used polyvinyl alcohol and sodium alginate, which are less expensive and harmful than agar and polyurethanes, to create gel beads for the various types of microalgae. First, a small amount of polyvinyl alcohol (2% w/v), sodium alginate (1% w/v), and soil supernatant was mixed with water and heated at 80 °C until the chemicals were dissolved. Silicon sand and 1.342 g each of deactivated microalgae biomass were added slowly into the mixture and mixed with SRB inoculum (20 ml) of active growth phase cells at 30–40 °C. The gel was slowly added to a cross-linker with a syringe and held at room temperature for 24 hours to make gel beads. Finally, the beads were cleaned with salt water three times to remove the boric acid and kept at 4 °C for future tests. With hydrolysis and fermentation, bacteria broke down the microalgae and then used it as a carbon source for SRB. Newly made SRB beads that can't move have strong structure and mass transfer ability and do better sulfate reduction than SRB that can move around. Immobilized SRB-Scenedesmus obliquus beads, dots stuffed within the up-flow bioreactor, were reasonable for the treatment of Cu(II) wastewater, as evidenced by the high removal productivity of their sulfate (182.17 mg SO42- g-1 microalgae day-1) and copper particles (45.28 mg Cu2+ g-1 microalgae day-1) and low release of COD. After the response, metal sulfides were not generated on the bead surfaces but likely inside them. The anaerobic bioreactor, filled with immobilized SRB-Scenedesmus obliquus beads, illustrates excellent removal efficiency and low release of COD, which may be a promising procedure for managing HM contamination in water (Li et al., 2018).

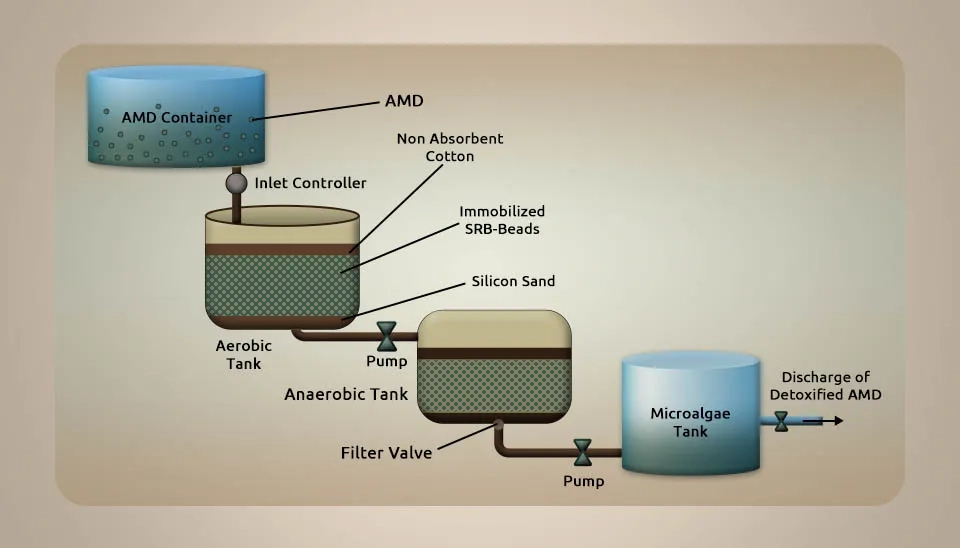

2.14. Microalgae— Chlorella, Bacteria— Enterobacter sp. AMD01

Sahoo et al. (2020) investigated an integrated bacteria-algae bioreactor for removing toxic metals in acid mine drainage from iron ore mines. An Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) test was collected from an iron ore mine within the mine’s locale of Odisha in India. The test was centrifuged at 1500 rpm at 20 °C. A volume of 10 ml of liquid was passed through a 0.22 µm syringe filter, followed by digestion with 100 µL NH₄⁺-N and heating on a hot plate at 70 °C for 20 min. 3 ml of supernatant was left to cool at room temperature for 30 minutes. Then, the volume was brought up to 10 ml with deionized water. We checked the tests for bacterial growth in an exceptional sulfate-rich environment, both under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Various types of SRB isolates were grown in a modified Postgate-B culture medium. The ferrous sulfate mixture was made with autoclaved water that had a pH level of 7.0. It was then put through a 0.2 µm syringe filter after being incubated at 30 °C and 100 rpm. In short, 5 ml of the test was drawn after 24 h of incubation and centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 10 min, followed by filtration through 0.22 µm to remove any residue and bacteria from the arrangement. 1 ml of filtrate was mixed with 5 mg of BaCl2 powder and 50 µL of conditioning reagent solution. The blend was placed on the vertex for 30 seconds. Milli-Q water was used as the standard for comparison. Absorbance at 420 nm was used as a standard curve for Na2SO4 for measuring residual sulfate. The toxicity of AMD in rice seedlings leads to irregular growth and development. Concentrations (mg L-1) of Mn (1671.17), Cu (84.55), Al (4530), Ti (834.97), Si (1974), S (1028), and Fe (12462) were identified in AMD. A coordinated microalgae-bacteria consortium for wastewater treatment technology was formed. This consortium effectively removes more than 95% of HMs from AMD after 48 hours of treatment after microalgae culture by increasing DO from 3.78 mg L⁻¹ to 6.7 mg L⁻¹. Germination (%) of rice seed was found to be highest with detoxified AMD and control conditions appearing at 94.55% and 94.44%, respectively, while 53.32% of germination was with AMD. We measured the amounts of catalase and peroxidase activity in a control sample, AMD that had been detoxified, AMD, and CuSO4.5H2O. The levels were 80.52 · 90.10 ^ 127.93 ^ 152.59 for catalase and 2.18 ^ 2.46 ^ 2.60 ^ 3.36 for peroxidase. The harmful effects of treated AMD on rice seedling roots are minimal compared to untreated AMD (Sahoo et al., 2020).

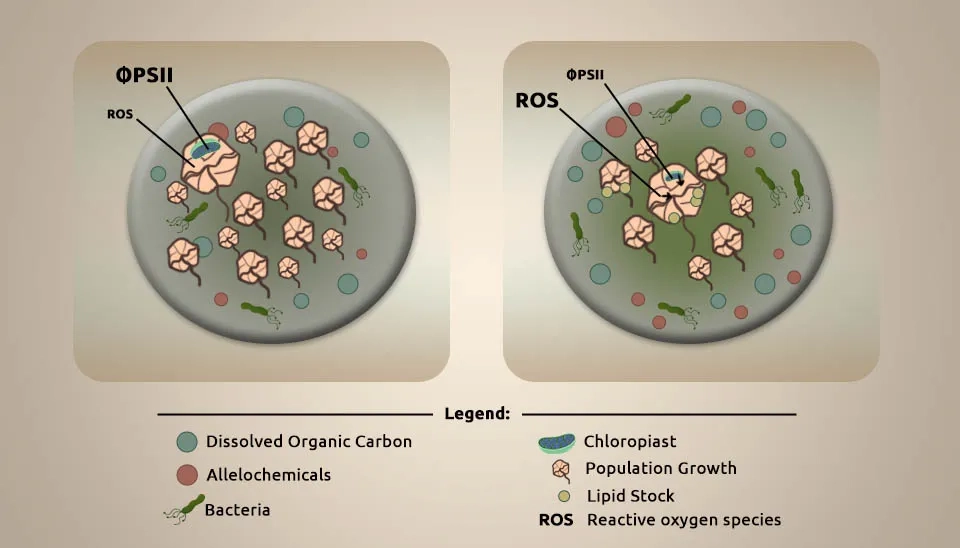

2.15. Microalgae— Alexandrium minutum; Free Bacteria

Long et al. (2019) studied the effects of copper on the dinoflagellate Alexandrium minutum and its allelochemical potency. All refined crystals utilized in toxicity tests were coated in a salinizing solution to avoid Cu losses due to adsorption into jars during toxicity samples. The culturing glassware employed in the Cu presentation was nitric acid washed for a slight test of 24 hours. A Cu stock arrangement (15.7 mM) was arranged in ultrapure water from CuSO4.5H2O in fermented ultrapure water. A 157 µm solution of Cu was made by mixing the robust solution with very ultrapure water. We collected seawater for Cu exposures from Australia, which had a salinity of 35.9 and a pH of 8.16, to test copper exposure. Seawater was filtered (0.2 µm) and autoclaved. According to its allelochemical potency, cultures of A. minutum strain CCMI1002, isolated from a bloom in Gearhies, were grown in natural seawater and added to F/2 media. Societies of A. minutum were kept under exponential development through weekly culturing and were kept at 17 ± 1 °C beneath white light with a 12:12 D/L cycle and light intensity of 150–210 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹. A. minutum were immunized within the sample media of natural seawater provided with NO3- (15 mg L⁻¹), PO43- (1.5 mg L⁻¹), and 1/5 of the F/2 vitamin concentration. The sample medium was inoculated with Cu (5000 cells ml⁻¹ day⁻¹) to let the culture decrypt from centrifugation at pH = 8.25. Cultures were carefully dealt with and pipetted to relieve cyst formation due to mechanical stress. Cultures were exposed to different treatments with distinctive beginning Cu concentrations: a control, natural, low, and high with no Cu, 7 ± 1 nM, 79 ± 6 nM, and 164 ± 6 nM, respectively. Every day, blending maintained a strategic distance from CO2 restriction in cultures with pH 8.07-8.25 during the exposure. We collected tests for dissolved Cu analysis 2 hours after the Cu spike, as well as 7 and 15 days after presentation. The highest Cu presentation (164 nM) restrained and delayed the growth of A. minutum, and only in this treatment did the allelochemical strength significantly increase while the dissolved Cu concentration remained harmful. Inside the primary 7 days of the high Cu treatment, the physiology of A. minutum was excessively impeded with decreased growth and photosynthesis, expanded stress reactions, and free bacterial thickness per microalgae cell. After 15 days, A. minutum somewhat recovered from Cu stress, as highlighted by the growth rate, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) level, and photosystem II yields. This recovery can be credited to the apparent decrease in foundation dissolved Cu concentration to a non-toxic level, recommending that the discharge of exudates may have mainly decreased the bioavailable Cu division. Generally, A. minutum showed itself to be very tolerant to Cu, and this work proposes that the adjustments in the physiology and within the exudates offer assistance to the microalgae to cope with Cu introduction. The complex interaction between abiotic and biotic factors can impact the dynamics of A. minutum blooms. Modulation of the allelochemical power of A. minutum by Cu may have biological implications for the increased competitiveness of this species in situations contaminated with Cu (Long et al., 2019).

3. Conclusion

Industrial improvement and social advances have caused the increasing pollution of HMs in water sources, influencing the aquatic ecological environment and affecting human health within the food chain. Accordingly, taking strategic measures to treat HMs present in wastewater at the start is essential to minimizing HM pollution for environmental sustainability and social welfare. Microalgae-bacteria consortia work together to improve the bioabsorption capacity of HMs, which can be widely used in microalgal-bacterial consortiums for heavy metal removal. The microalgae-bacteria consortium for wastewater treatment for HM has been successfully worked on under laboratory conditions, with preferences such as low cost and excellent removal efficiency. However, the research is still in the lab, and we haven’t done the related Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) yet. Using the MBC system to treat natural HM wastewater on a large scale still faces many challenges, and more study is needed. Using the MBC system to treat wastewater and its by-products together is essential. This procedure helps us understand how well the MBC system works in different ways, like using less energy, turning waste into energy, and returning valuable materials. Bacteria can change toxic heavy metals attached to algae so that they can be cleaned up by bacteria decomposing themselves, making the cleaning process more effective. In summary, the utilization of combined microalgae and bacteria for the microalgal-bacterial consortium for heavy metals removal offers numerous advantages, including high efficiency, economic feasibility, and simplicity. When microalgae and bacteria collaborate to treat wastewater, they can gather biomass energy for the production of various connected value-added products. However, there is currently no setup or technology for heavy metal removal by the microalgal-bacterial consortium with high biomass production. As a result, more research is needed into how MBC works to help with HM treatment and the response device to find a wide range of valuable applications with social and economic benefits. Generally, the MBC system has excellent potential for HM-containing wastewater treatment, but further research is required to address existing issues and advance its large-scale application.