Ever pondered the transformative power of microalgal-bacterial consortiums in revolutionizing nutrient removal within the intricate framework of wastewater treatment systems?

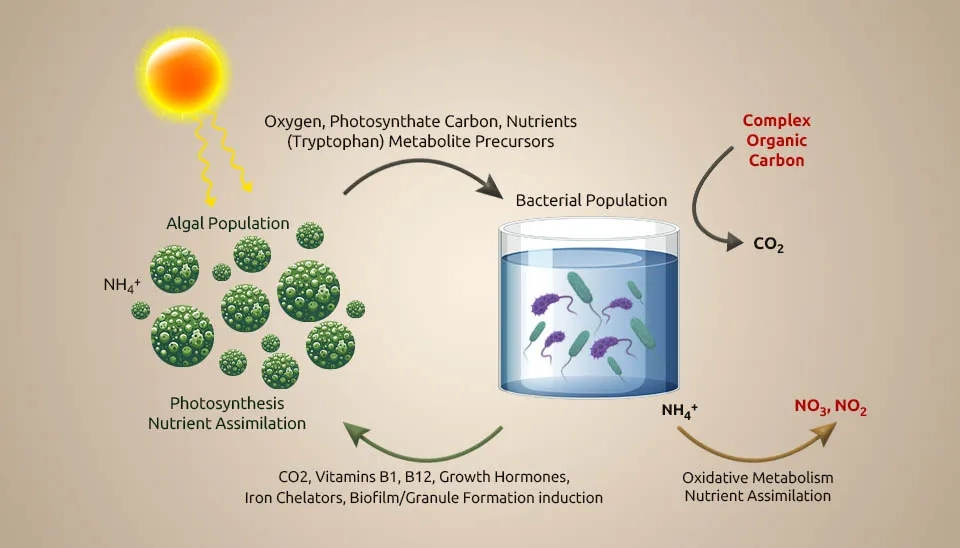

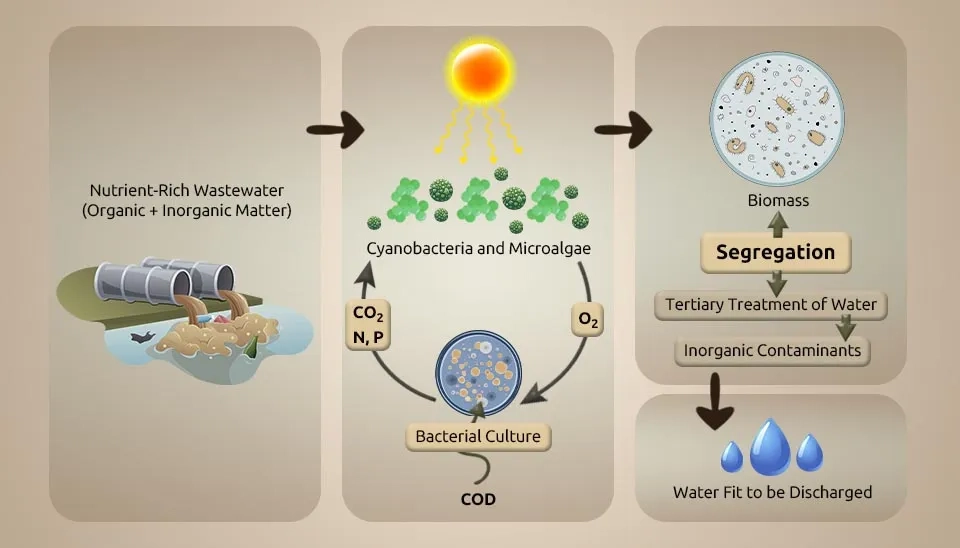

Microalgae-bacteria consortia (MBC)-based treatment systems are a promising bioremediation step because microalgae can make oxygen on their own when exposed to light (photooxygenation), lowering the cost of running mechanical air circulation systems. This oxygen generation provides the necessary conditions for heterotrophic bacteria (HB) to oxidize chemical oxygen demand (COD) and for nitrifying bacteria (NB) to convert ammonium into nitrate (NO₃⁻) during the nitrification process. In this way, HB produces CO₂, which microalgae and NB use as a carbon source. MBC systems have a high capacity for nutrient removal. This capability is often the result of the ability of microalgae to absorb nutrients and the mechanisms related to NB. MBC can revolutionize conventional wastewater treatment by using sunlight as an energy source to drive the biological process. In this way, operating costs are reduced, and potentially valuable products can be obtained from wastewater by converting biomass into biofertilizers, biofuels, and bioproducts. Additionally, the absorption of CO2 by microalgae reduces its emissions compared to conventional activated sludge (CAS). The MBC plant effluent is expected to discharge treated effluent and meet recycling standards (Oviedo et al., 2023).This study investigates Microalgae-Bacterial Consortia in Wastewater Treatment to enhance nutrient removal efficiency.

This article discussed the nutrient removal mechanism from wastewater using MBC.This study investigates Microalgae-Bacterial Consortia in Wastewater Treatment to enhance nutrient removal efficiency.

Table 1. Microalgal-bacteria consortium on various types of wastewaters for nutrient removal

Microalgae species | Bacteria species | Nutrient removal |

|---|---|---|

Chlorella, Chroococcus sp., Scenedesmus sp., Oscillatoria sp. | Activated sludge bacteria | NH4+-N:99% PO4-3-P:100% |

Chlorella and diatoms | Filamentous cyanobacteria and heterotrophic bacteria | TN:12.6% TKN:97% TP: 47% |

Download Full Table of 26 Microalgal-Bacterial Consortia for Nutrient Removal in Wastewater Treatment Systems

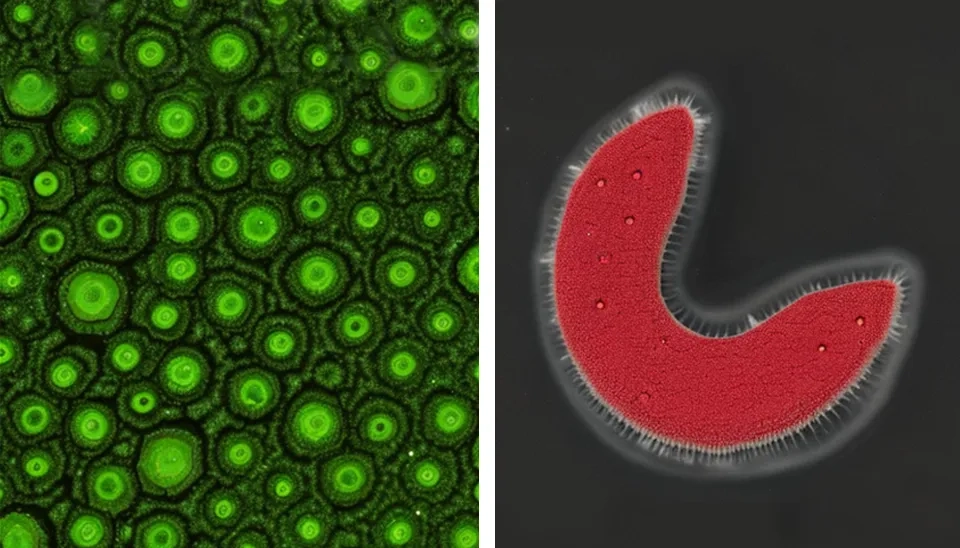

Nitrogen and phosphorus are two of the most critical components causing eutrophication in water bodies and are significant components of proteins (Khan et al., 2023). Microalgae are considered a perfect strategy for nutrient contamination control in wastewater due to their high efficiency in nitrogen absorption and high protein content. However, harvesting and separating microalgae from water bodies is challenging. Due to its productive sedimentation in the consortium of microalgae-bacteria in wastewater treatment, it has become a potential arrangement for nitrogen removal and protein recuperation from wastewater (Zhang et al., 2023). The applications of the Microalgae-Bacteria Consortium (MBC) in wastewater treatment can be traced back to 1952, with high-efficiency MBC as the most well-known method. Due to the poor settling performance of MBC flocculant and the trouble of isolating it from the wastewater, using the MBC method advances slowly. After discovering that the MBC floc could achieve high settling capacity by controlling the bacterial-microalgae ratio, the method began to rapidly develop in 2012. In the past few years, MBC has made surprising advancements in improving nitrogen-removal efficiency for various wastewaters, including domestic sewage, pig farm wastewater, and even aquaculture water (Fallahi et al., 2021). In this article, we'll acquaint you with 26 remarkable compounds dedicated to nutrient removal, undoubtedly reshaping your perspective on sustainable purification. Also, this study delves into the world of advanced and environmentally friendly solutions, focusing on the potential of microalgal-bacterial systems to significantly transform the process of nutrient removal in wastewater treatment.

1. Interactions Between Microalgae and Bacteria

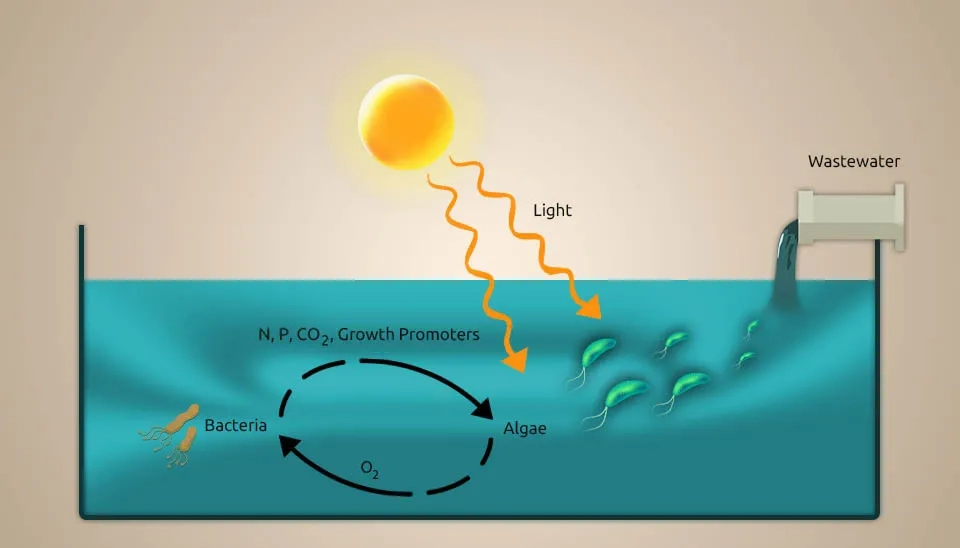

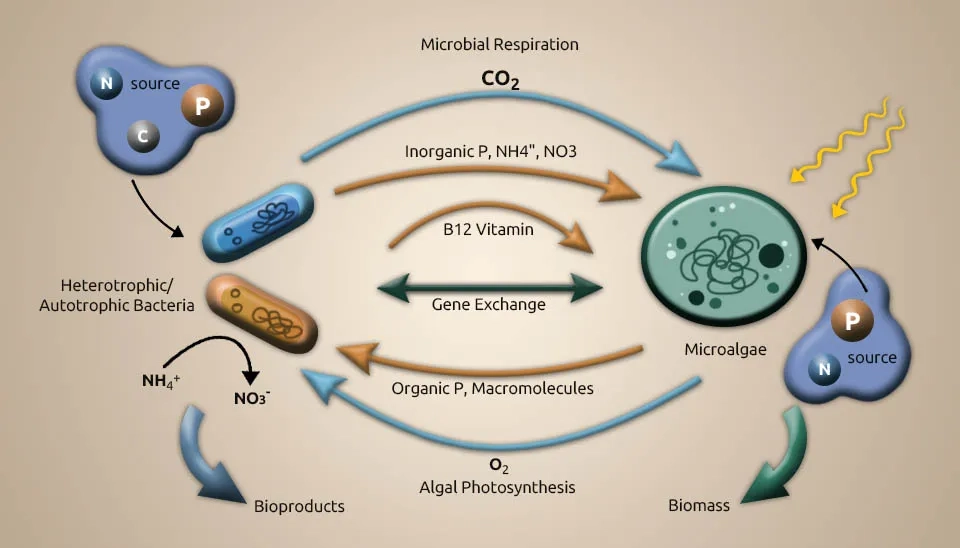

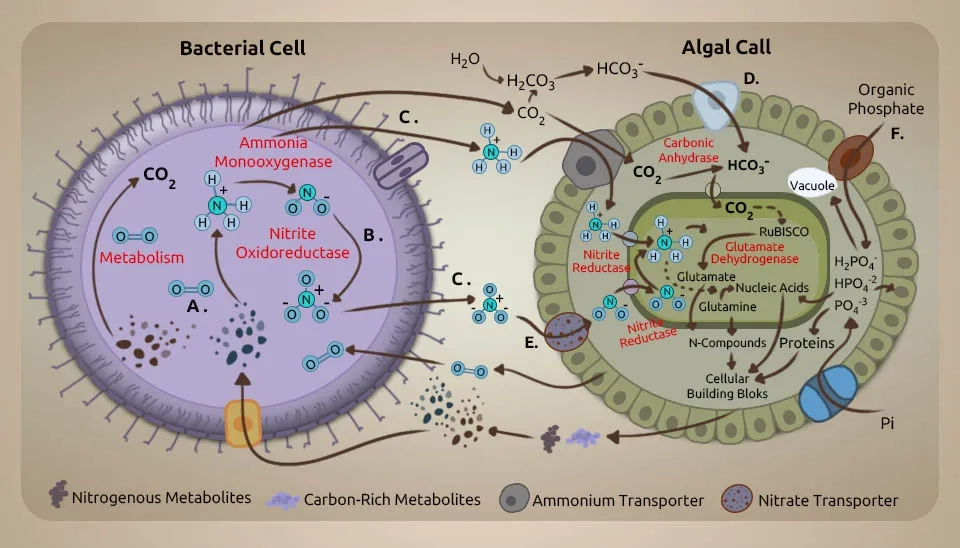

Due to the wastewater discharge of rivers, seas, and oceans, each year, a lot of phosphorus and nitrogen enter natural water bodies (Bi et al., 2019). In biological wastewater treatment systems, microalgae, as tiny aeration devices, help other bacteria by producing oxygen and fixing CO2. It causes eutrophication and harms the environment. The oxygen production by microalgae can help establish a relationship between them and anaerobic bacteria during wastewater treatment. Also, the oxygen production by microalgae can help bacteria during the breakdown of organic carbon, and the carbon dioxide produced during this degradation and bacterial respiration provides essential carbon for microalgae photosynthesis. Using microalgae in denitrification processes requires careful culture management to control the dissolved oxygen (DO) level (Jia & Yuan, 2017). Moreover, synergistic interactions between microalgae and bacteria in consortia can share important metabolites to meet their nutritional requirements (Nagarajan et al., 2022). Microalgae-bacteria interaction in wastewater treatment can help recycle nutrients toward a sustainable bio-economy (Nguyen et al., 2021).The microalgae-bacteria interaction in wastewater treatment creates a synergistic environment for nutrient removal.

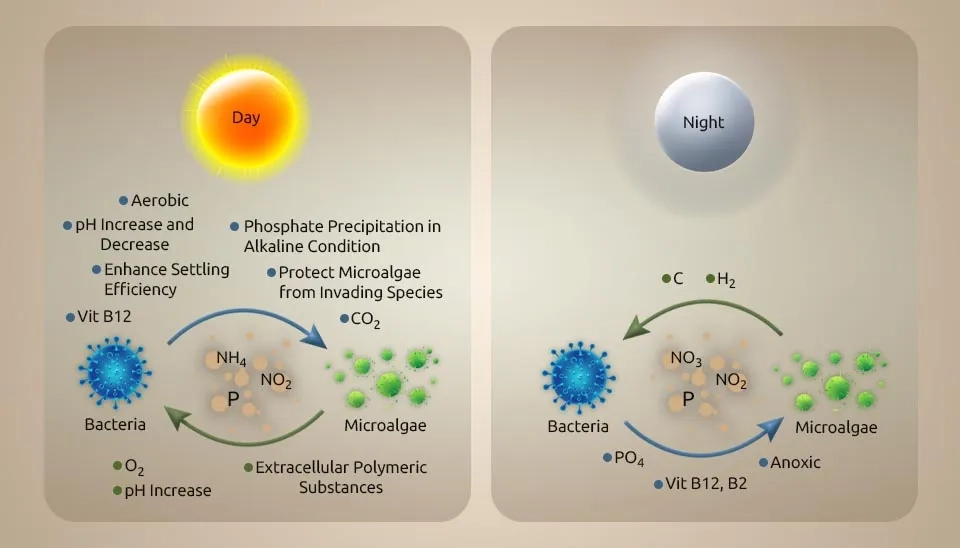

Other than oxygen and carbon dioxide trade, the interactions between microalgae and bacteria incorporate other aspects such as growth promotion, extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) production, extracellular production, and pH decrease or increase, which demonstrates the potential of microalgae-bacteria interaction in wastewater treatment (Rezvani et al., 2018). Hydrogen gas is profoundly dangerous, has low dissolvability, and is costly to utilize in autotrophic denitrification processes (Karanasios et al., 2010). In situ generation of hydrogen gas is an elective arrangement for this issue. The capability of certain microalgae strains to make hydrogen gas, particularly in the presence of bacteria, has already been well recognized (Cho et al., 2019). Regarding wastewater, research on microalgae-based treatments has been conducted for over half a century. Waste Stabilization Pond Systems (WSPs) and High-Rate Algal Ponds (HRAP) are currently accessible innovations. A WSP is an open framework where microalgae and heterotrophic bacteria form an advantageous relationship, as shown in Fig. In this framework, microalgae absorb nutrients, and bacteria remove natural matter. An HRAP is a shallow, paddlewheel-mixed open raceway pond. In this system, microalgae grow quickly and produce a significant amount of oxygen, driving aerobic treatment and the absorption of wastewater nutrients in algal biomass. The end conclusions from the microalgae-based treatment can be utilized as creature feed or crop fertilizer (Craggs et al., 2014).

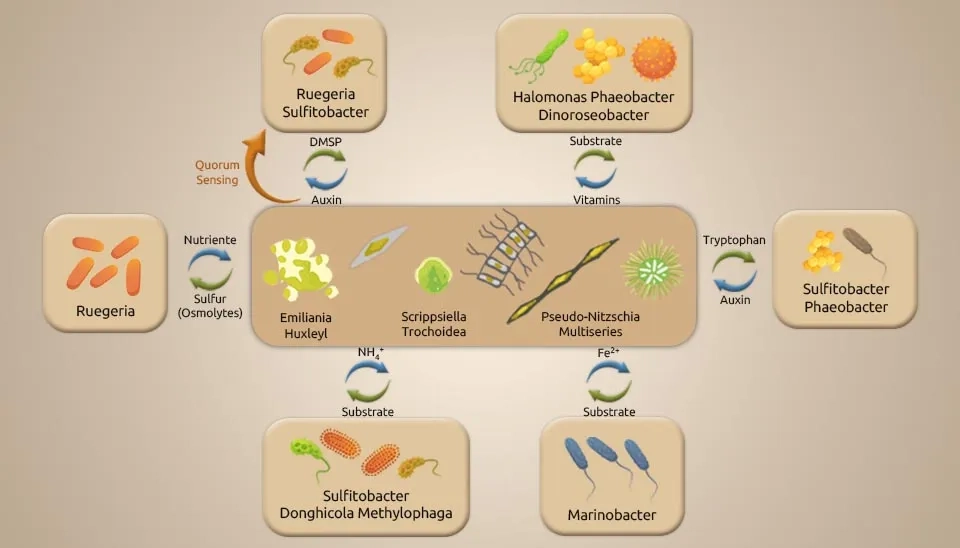

A comprehensive understanding of the interaction between microalgae and bacteria is fundamental to improving treatment execution, such as by increasing total nutrition removal. Microalgae and bacteria interact in different ways, from mutualism to antagonism. Microalgal and bacterial communities interact based on energy and nutrition trade, flag transduction, and gene exchange. A few cofactors that are imperative for metabolic processes by microalgae and bacteria are Microalgae generate oxygen (O₂) for bacteria to utilize as an electron acceptor and energy source to remove organic matter, whereas algae use carbon dioxide (CO₂) from bacterial respiration as the carbon source (Chan et al., 2022). The antagonistic impact may happen in a dark condition when microalgae and bacteria compete for oxygen in the respiratory process and due to the deterioration of dead cells. Microalgae generate hydrogen in the dark in low-oxygen environments through a process called denitrification. During the day, photosynthesis modifies the carbon stores that control hydrogen generation at night. In addition to the light/dark cycle, letting microalgae grow to very high biomass levels can also cause self-shading because a low-oxygen environment is suitable for making hydrogen (Rezvani et al., 2020). Without the injection of external hydrogen gas, the bacteria-microalgae consortium achieves the highest nitrate removal rate per large biomass. Vitamin B is imperative to the beneficial relationship between microalgae and bacteria. Additionally, vitamin B12 is delivered by bacteria either in aerobic or anaerobic conditions. Vitamin B12 helps control microalgal growth and community composition (Blifernez-Klassen et al., 2021). Azospirillum brasilense and Chlorella vulgaris were immobilized and grown together. This caused Chlorella vulgaris to grow faster because Azospirillum brasilense makes riboflavin and lumichrome (vitamin B), which Chlorella vulgaris needs to develop and use. In addition to shared development, microalgae and bacteria show bactericidal and algicidal impacts separately toward certain species (Ramos-Ibarra et al., 2019).

pH increases through microalgae photosynthesis, whereas bacteria metabolism generates organic acid to decrease the pH. These complex interactions between microalgae and bacteria in the phycosphere differ from how they behave in their surrounding milieu. Facilitating periods of low oxygen for denitrification can be a tool for the light-dark cycle and culture density management (Chochois et al., 2009). Using biomass assimilation, microalgae can remove many of the nutrients in wastewater. Therefore, collecting as much harvest efficiency of microalgae and bacteria biomass from the mixture as possible is essential to ensure the wastewater achieves a high-quality effluent. Biomass harvesting from wastewater can usually be difficult because the cells are tiny in size, the cell density is similar to water, the concentration of the cell suspension is low, and the cells settle slowly (Huang et al., 2020).

Produced compounds by many types of bacteria, such as polysaccharides or proteins, help to increase microalgae bio-flocculation and make it easier to do floc. On the other hand, microalgae can create a range of inhibitory compounds that can interfere with bacteria's growth. For example, microalgae can create EPS, which restrains bacterial growth. Microbial cell dividers excrete EPS, a mixture of carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, glycoproteins, and phospholipids. Complex intelligence like London strengths, electrostatic intuition, and hydrogen holding help EPS stick to the solids' biomass and keep them together. This chemical reaction is what sets the flocs in place. These properties of EPS make it reasonable for numerous applications such as sludge flocculation, settling, dewatering, metal binding, and the removal of harmful natural compounds (Nouha et al., 2018).

On the other hand, algicidal bacteria can deliver destructive microbial substances like cellulase to deteriorate the cell walls of microalgae cells and lyse them. Therefore, choosing appropriate species for the microalgae-bacteria advantageous system is fundamental. Some microalgae have a better level of bacterial interaction than others. Blending expanding proportions of activated sludge bacteria with microalgae may abbreviate the settling time of the suspension. Bio-flocculation production in bacteria-microalgae systems is considered an economical, non-toxic, and cheap approach for biomass and nutrient recuperation (Khan et al., 2018). The Microalgae-Bacteria Consortium (MBC) system can remove other materials, such as heavy metals, pesticides, and herbicides, which we will not discuss in this article.

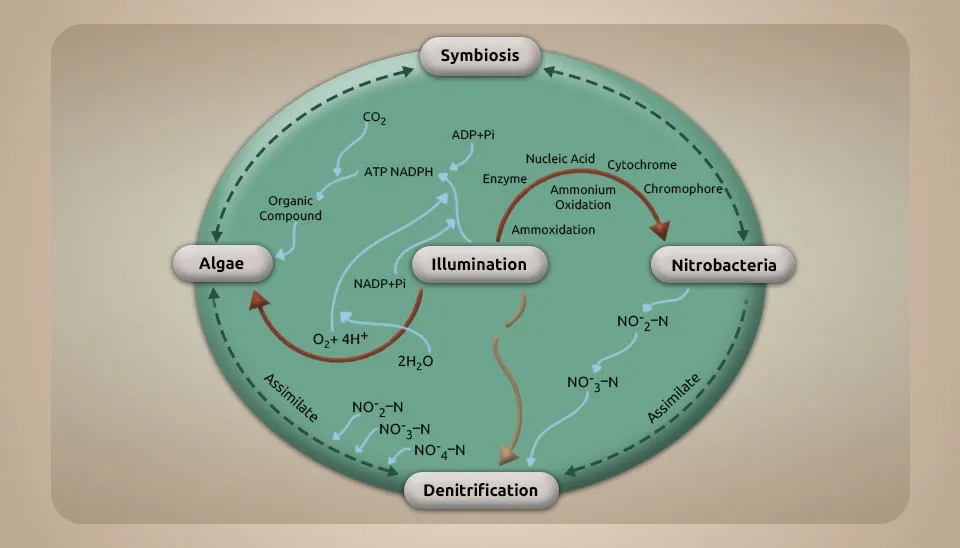

1.1. Nitrogen Removal Mechanisms

Microalgae absorb nitrogen through reductase enzymes and transporters inside their cells. The main benefit of the microalgae-bacteria consortium system is that different organisms work together to help each other grow and thrive. Microalgae can use ammonia to make oxygen through photosynthesis in their combined synergistic metabolism. Bacteria consume oxygen to change ammonia and nitrite and release carbon dioxide. These symbiotic relations have been used in open ponds or closed photobioreactors to achieve enhanced removal of nutrients and organic carbon (Qu et al., 2021). The microalgae-bacteria interaction in wastewater treatment removed NO3−-N and COD, which were ultimately absorbed and utilized as well, and the removal rates of PO4-3-P and NH4+-N were 99.82% and 87.13%, respectively (Chen et al., 2019). This synergetic interaction also caused a fast nitrification process. The microalgae-bacteria interaction in wastewater treatment systems can remove 60–80% of ammonia in just 1 to 2 days of hydraulic retention time, whereas pure-microalgae systems require 2 to 5 days (Maza-Márquez et al., 2018).

There could be competition between the microalgae and the ammonia-oxidizing bacteria when it comes to removing ammonium from wastewater. Microalgae use NH4+-N instead of NO3--N to increase their biomass. As a result, the NO3--N consumption is lower than the NH4+-N consumption. So, decreasing the TN concentration in wastewater mainly depends on how well microalgae can absorb NH₄⁺-N. The levels of NO3−-N are going down, which is happening because of microalgae growth and nutrient consumption. Bacteria play a significant role in the natural nitrogen process. They can perform the tasks of heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification. This process happens when there is a high carbon/nitrogen ratio (C/N) in the wastewater or enough oxygen in the environment. Chemoautotrophic denitrifying bacteria require inorganic matter such as hydrogen gas to control nitrate reduction, which microalgae can provide (Qv et al., 2023). The main reason the TN removal efficiency is lower is that the time it takes to grow the microalgae is shorter, and there is less microalgae biomass. Bacteria are connected to how carbon and nitrogen are processed in nature. Some species can do aerobic denitrification under a certain C/N balance. Other bacteria uniquely process carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycles called Denitrifying Sulfide Removal (DSR). They use organic material and sulfide to generate energy (Zurano et al., 2020).

The removal of TN from the wastewater is accomplished by changing the ammonia nitrogen to the nitrate nitrogen form through nitrification by Ammonia Oxidizing Bacteria (AOB) and denitrification due to the presence of activated sludge. Despite the low input concentrations, the N-NO3− is still visible at the outlet of the wastewater plant, probably because it was not consumed entirely by microalgae and bacteria or because it is generated by nitrifying bacteria (Fallahi et al., 2021). Given the concerns concerning the low nitrogen concentrations at the wastewater outlet, it was conceivable to affirm that the proposed microalgae wastewater treatment complies with the effluent release limits (European Directive 91/271/CEE). Unlike monoculture systems, denitrification is a key process that enhances the removal of TN in the Microalgae-Bacteria Consortium (MBC) system. All bacteria could contribute to the high removal rate of COD, whereas a portion of the bacteria may contribute to the aerobic removal of nitrogen and phosphorus (Wang et al., 2023). Denitrifying bacteria are needed to remove nitrogen through specific biochemical reactions in anoxic or anaerobic conditions. Denitrifying bacteria, which are mostly heterotrophic microorganisms relying on organic sources for food, need sufficient carbon sources to effectively remove nitrogen. So, using existing carbon sources or carbon sources can help denitrify bacteria and remove TN more effectively in the Microalgae-Bacteria Symbiosis (MBC) system. The high removal rates for NH3-N and TP levels may be because of the efficient absorption of the nutrients by microalgae, particularly when the CO₂-rich air was given. When microalgae oxygen is produced in photosynthesis, it enhances the removal of NH3-N in microalgae-bacteriostatic symbiosis (MBS) systems. However, this oxygen can also prevent the removal of TN (Ye et al., 2016).

1.2. Phosphorus Removal Mechanisms

Microalgae treatment after the improved biological phosphorus removal process and phosphate precipitation are two mechanisms for phosphorus removal in the microalgae-bacteria consortium system. The PO4-3 and CO2 created by bacteria can be converted to oxygen by microalgae in this system (Higgins et al., 2018). Phosphate precipitation of the wastewater happens during the day because of microalgae photosynthesis. The process of photosynthesis in microalgae causes a change in the pH of the environment. Each nitrate ion breaks down into ammonia and produces one hydroxide ion. Hydroxide ions help bacteria to release compounds that destroy microalgae. Algaecides combat microalgae, leading to the release of EPS. The release of EPS led to the precipitation of phosphorus (Sells et al., 2018).

Phosphorus plays a vital role in the metabolism of microalgae and bacteria because it can be made into organic molecules such as DNA, RNA, and lipids through phosphorylation. Phosphorous removal presents a similar pattern, such as N-NH4+ removals. Thus, when P-PO₄⁻³ in the inlet increased, phosphorous removal efficiency also increased. The lower amount of PO₄⁻³⁻P in the bacteria can be explained by too much phosphorus clumping together because of the bacteria's size, ability to take in extra energy, biochemical makeup, and increased cell energy-generation responses (Yoo et al., 2015). Absorption and deposition are the two main ways of removing P from wastewater. Adding a small amount of chemical flocculant to HRAP system effluent before the microalgae harvest tank can reduce phosphorus concentrations in sewage. The removal efficiency of TP in the microalgae monoculture systems gradually increased as the cultivation time proceeded (Young et al., 2021).

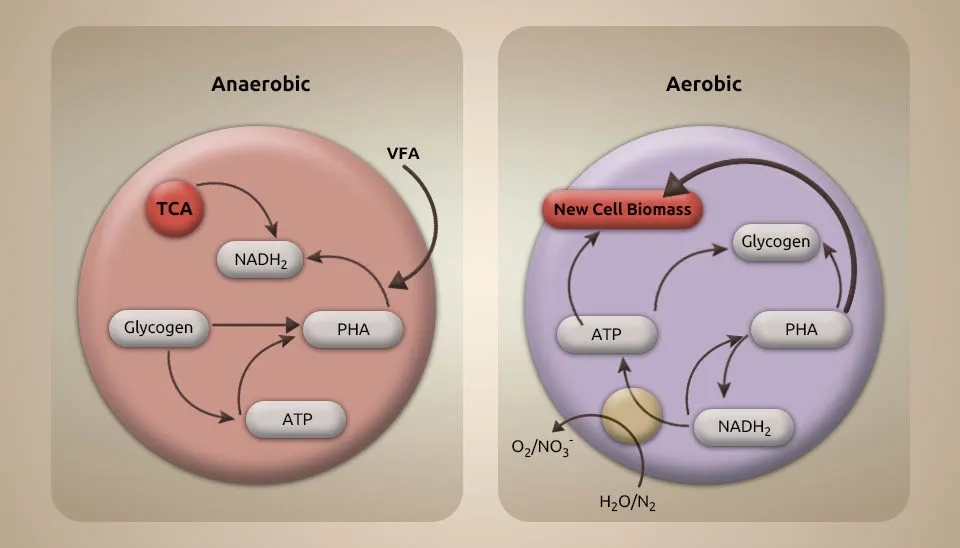

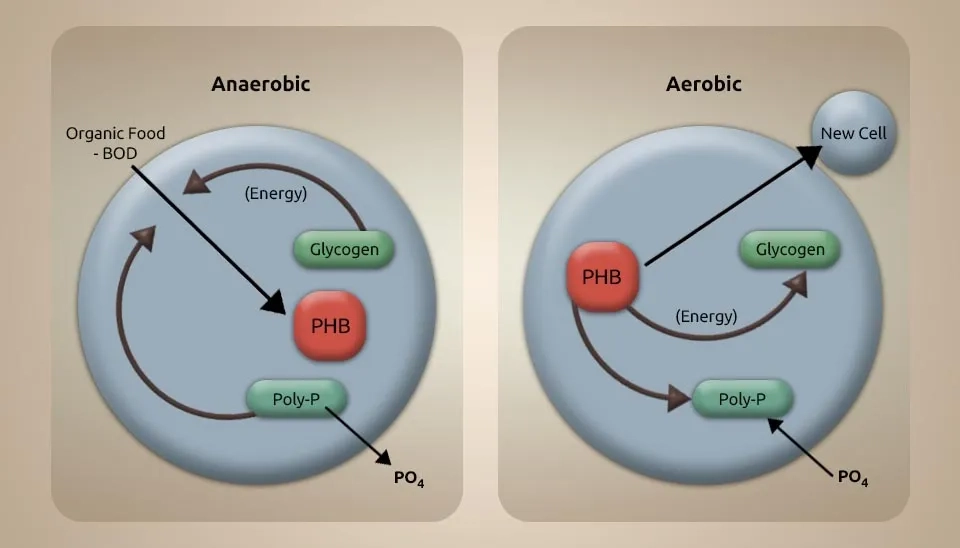

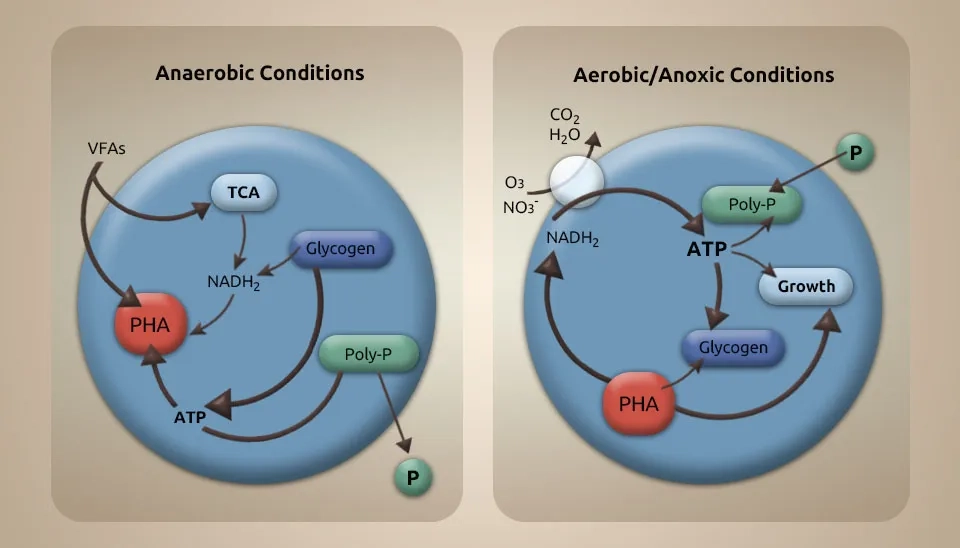

The activated sludge system did not work well in TP removal, and the removal efficiency was inconsistent and unstable. This was because the instrument of P removal by the activated sludge system contained two processes: uptake and discharge of P by polyphosphate-accumulating organisms (PAOs). The PAOs corrupt intracellular polyphosphates (poly-P) beneath anaerobic conditions, discharging them into wastewater as PO4-3-P. A short time later, PAOs take up the organic carbon source as intracellular carbon polymers, namely poly-β-hydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), with the energy produced by the decay of glycogen and poly-P (Oehmen et al., 2007). The symbiosis of microalgae and bacteria does not improve TP removal performance, possibly because microalgae expansion does not boost PAO proliferation. In any case, the higher action of microalgae in the symbiosis system permits the control of DO and pH by O2 discharge from photosynthesis, and the P removal in the MBC system is steadier within the afterward stages of the cultivation (Yazdanbakhsh et al., 2023)

2. Introducing 26 Varieties of Microalgal-Bacterial Consortia for Nutrient Removal in Wastewater

This study investigates Microalgae-Bacterial Consortia in Wastewater Treatment to enhance nutrient removal efficiency. and discusses various projects carried out recently and introduces microalgae and bacterial types.

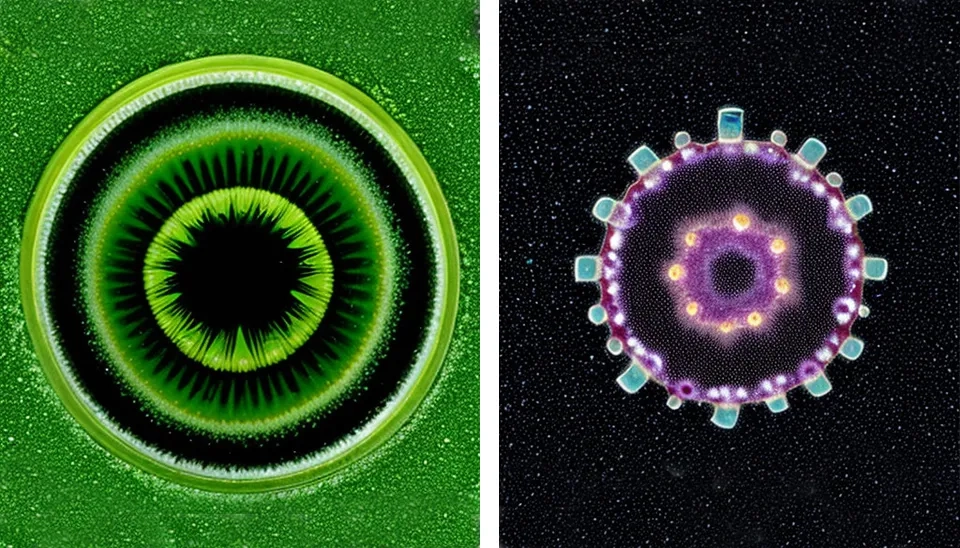

2.1. Microalgae (Chlorella, Chroococcus sp., Scenedesmus sp., and Oscillatoria sp.) and Bacteria (Activated Sludge)

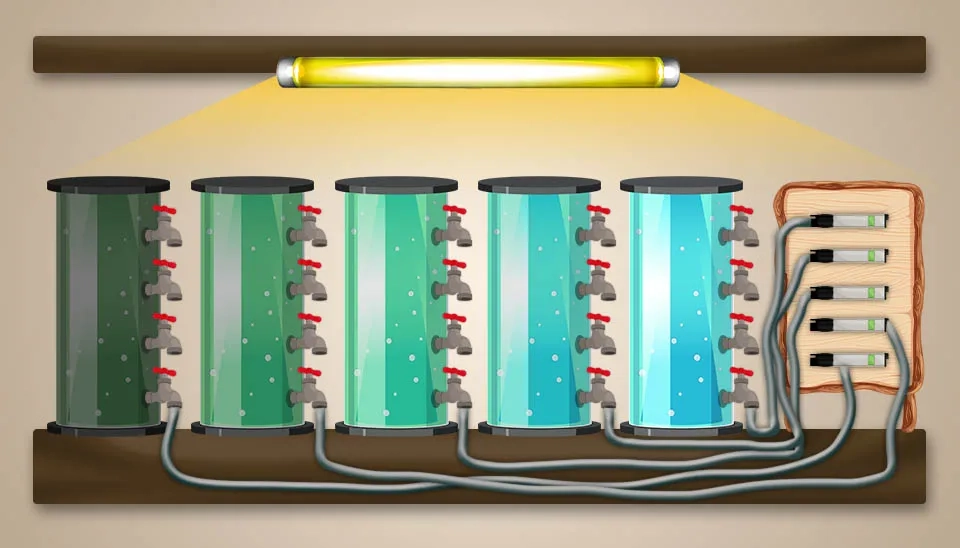

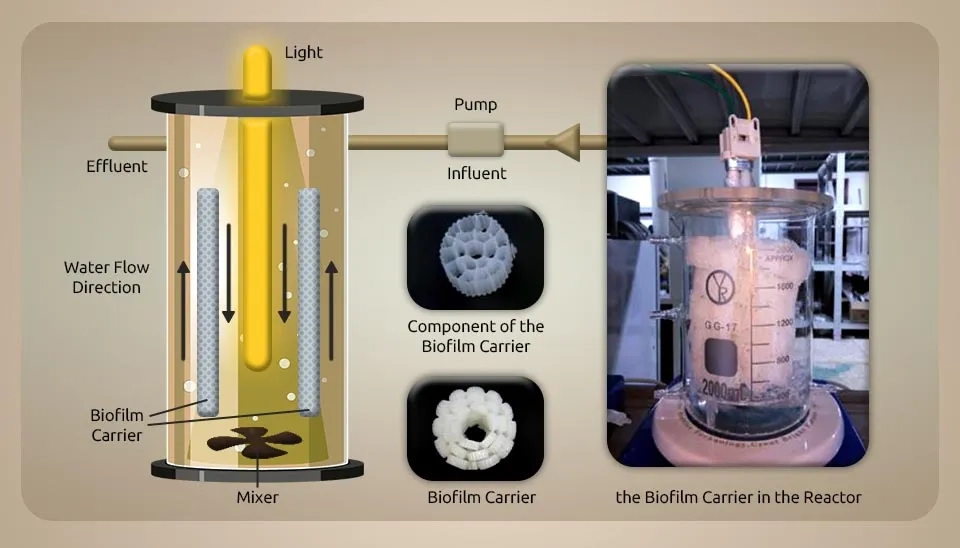

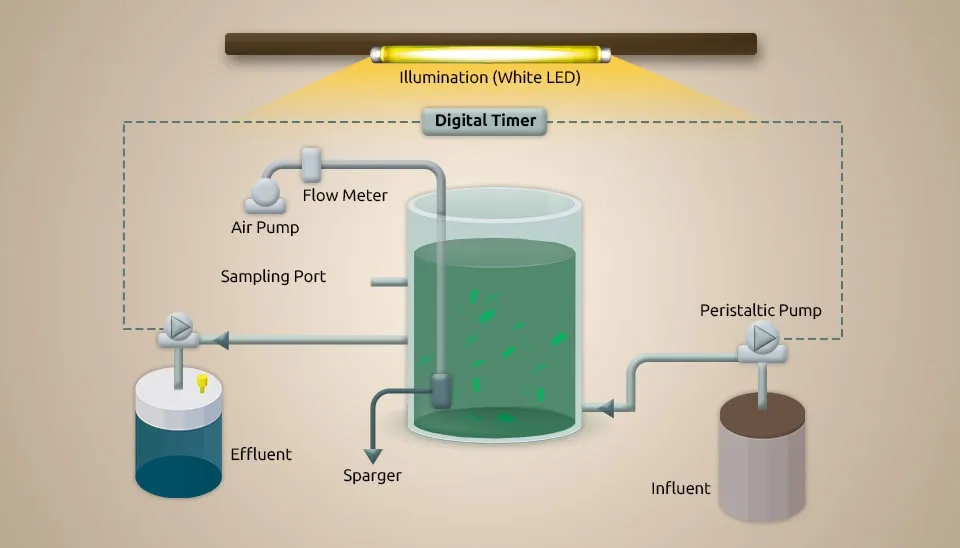

( Gou et al., 2020) constructed a biofilm reactor of microalgae-bacterial consortia in wastewater treatment. The characteristics of this bioreactor are shown in the figure below. The volume, light intensity, mixer speed, temperature, and biofilm carrier (polyethylene) were 2L, 200 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹, 100 rpm, 28 °C, and 20 mm in synthetic wastewater, respectively. The COD, NH4+-N, and PO4-3-P concentrations were 300 mg L-1, 40 mg L-1, and 10 mg L-1, respectively. The wastewater treatment plant collected bacteria and microalgae from the activated sludge (AS) and the secondary settler's divider. The reactor's beginning sludge and microalgae concentrations were 900 mg L⁻¹ and 900 mg L⁻¹, respectively. MBC systems need high hydraulic retention times (HRTs, 2–10 days) to efficiently remove pollutants from domestic wastewater. Gou et al. made a new type of MBC biofilm reactor to decrease HRT. They indicated that the removal of ammonium and phosphate is 90% and 30%, respectively, when HRT is 12 hours. Reducing and increasing the HRT to 8 and 24 hours did not improve removal efficiencies. An LED light provides the light source for microalgal growth. In fixed DO concentration (2 mg L⁻¹), the organic matter and ammonium removal rates were 70% and 50%, respectively. The removal efficiency of COD was 18.63 mg COD L-1.h-1 and 25.35 mg COD L-1.h-1 from illumination and aeration. Also, the removal efficiency of phosphate was 0.26 mg L⁻¹ h⁻¹ and 0.43 mg L⁻¹ h⁻¹ in illumination and aeration, respectively (Gou et al. 2020) .

2.2. Microalgae (Chlorella and diatoms) and Bacteria (Filamentous Cyanobacteria and Heterotrophic)

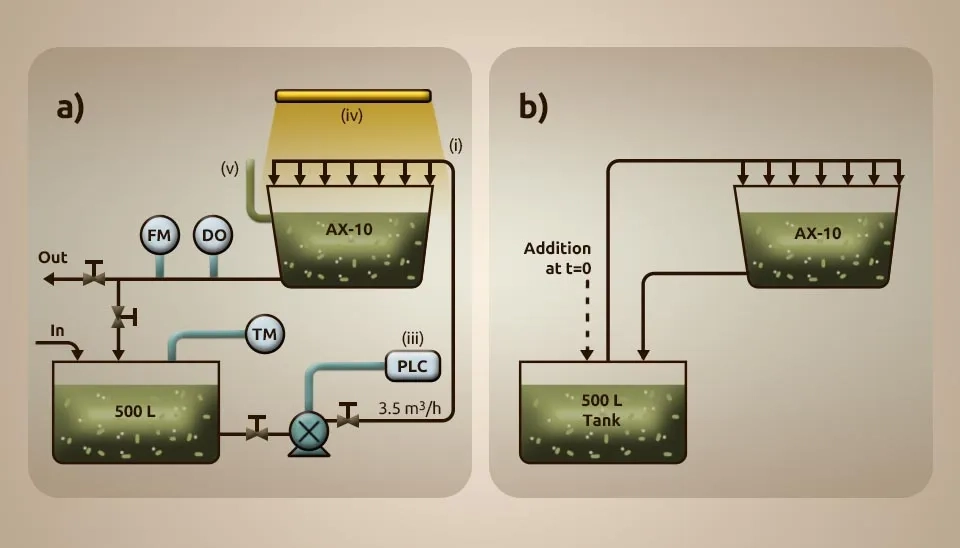

Foladori et al. (2018) investigated MBC to optimize total nitrogen (TN) removal from real municipal wastewater using a Photo-Sequencing Batch Reactor (PSBR). The figure below illustrates the characteristics of the PSBR. We collected influent municipal pre-settled wastewater from the Trento Nord WWTP's primary settler (100,000 PE) and nourished it in a lab-scale photobioreactor. We did not filter the influent wastewater before feeding it into the reactor. This allows the Bacteria that are normally found in the influent wastewater, it can get into the reactor and have a big effect on the MBC that is made in this system. The PSBR setup comprises a cylindrical bench-scale reactor made of Pyrex glass with a diameter of 0.13 m, a height of 0.29 m, and a working volume of 2 L. The system was equipped with a peristaltic pump for pumping the influent and discharging the effluent; 0.7 L of influent wastewater was discharged per cycle. A cool-white lamp with 8 LEDs × 0.5 W (0.18 m high and 0.065 m wide) was placed on one side of the PSBR. The magnetic mixer (200 rpm) maintains the biomass in suspension during the reacting phase, avoiding excessive turbulence and reoxygenation from the air. A lamp (30 μμmol m⁻².s⁻¹) was used inside the reactor near the top of the liquid surface and sun-oriented light. Due to the oxygen produced by microalgae photosynthesis, there was no external aeration in the PSBR, so it reduced energy consumption. The dark phase lacked oxygen and produced readily biodegradable COD, resulting in a high TN removal efficiency that facilitated denitrification. Continuous mixing and intermittent mixer use resulted in a 41% energy savings, favoring simultaneous nitrification-denitrification. The effluent concentration of COD was 257 ± 91 mg L⁻¹, and its total concentration reached 37 ± 7 mg L⁻¹ in this system, so COD removal efficiency was obtained at 86 ± 2%. With an ammonium concentration of 0.5 ± 0.7 mg NH₄⁺-N L⁻¹, TKN removal was obtained at 97 ± 3%. Absorption of nitrogen by heterotrophic bacteria accounted for 20% of TKN removal, while the central portion of TKN was nitrified. Specifically, the nitrification rate was 1.9 mgN L-1 h-1 (2.4 mgN gTSS-1 h-1), measured at DO near zero, when the oxygen request outperformed the oxygen created by photosynthesis. A TN of 6.3 ± 4.4 mgN L⁻¹ was observed within the effluent after PSBR optimization. The PSBR allowed the realization of nitrification of real municipal wastewater in laboratory conditions without the requirement of air circulation and with energy sparing, where synchronous denitrification improves add-up nitrogen expulsion.

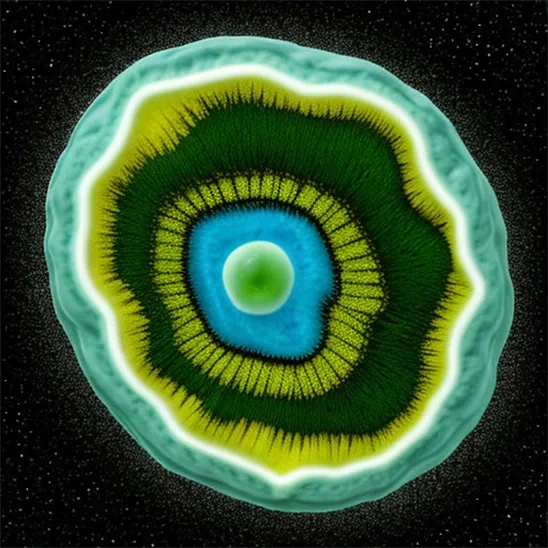

2.3. Microalgae (C. Sorokiniana) and Activated Sludge Bacteria (Rhodobacteraceae and Rhizobiaceae Families)

Barreiro-Vescovo et al. (2021) investigated the Microalgae-Bacteria Symbiosis (MBS) system using the semi-continuous operation of photo-bioreactors treating domestic wastewater and Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis (DGGE) techniques. The inoculum of Chlorella sorokiniana utilized within the measure was isolated from the photic zone of a secondary settler at the wastewater treatment plant of Castell´on de la Plana (Spain). The inoculum was pre-cultured for 7 days at room temperature beneath continuous illumination provided by 4 fluorescent lights (122 μmol m−2 s−1). Microalgae were blended by a magnetic disturbance (250 rpm), and 0.3 L of microalgae culture (1.31 g TS L−1) was pre-incubated until it was exchanged to the bioreactor. Bacteria were collected from the secondary treatment tank of the domestic wastewater facility of Castell´on de la Plana (Spain). Microalgae inoculum and 50 mL of the alcohol blend from the aeration tank (1.27 g L−1) were put into the bioreactor. The volumes of each inoculum brought about a mass ratio of 75/25 of bacteria and microalgae, respectively. Two encased, jacketed glass bioreactors with a combined working volume of 1 L and a total capacity of 1.65 L were utilized to assess the wastewater biodegradation and microbial community characterization. L/D cycles, temperature, and HRT were for 14/10 hours, 24°C, and 3 days, respectively. The operation continued for 23 days, achieving consistent conditions after 9 days. Tests of 0.1 L were intermittently used during the test period for biological characterization. Tests were kept at 4°C sometime recently in analytical methods.

The microalgae strains grow by the inoculated strain Chlorella sorokiniana; the bacterial community was entirely supplanted by microbial groups showing environmental adjustments. The evaluation conducted by flow cytometry proved bacterial population relocation favoring pigmented and photoheterotrophic groups. The Rhodobacteraceae strain is dominant during steady-state conditions, while the Rhizobiaceae strain disappeared during its presence in the inoculum. This finding was correlated with the DGGE analysis. This specific bacterial community composition was related to the constrained organic matter utilization identified within the exploratory reactors, as assessed by removal rates of 64.2 ± 4.8% of COD in primary treated wastewater. The dominance of photoheterotrophs and pigmented bacteria diminished the metabolic capability of the photobioreactor, resulting in deficient wastewater treatment for discharge regulations.

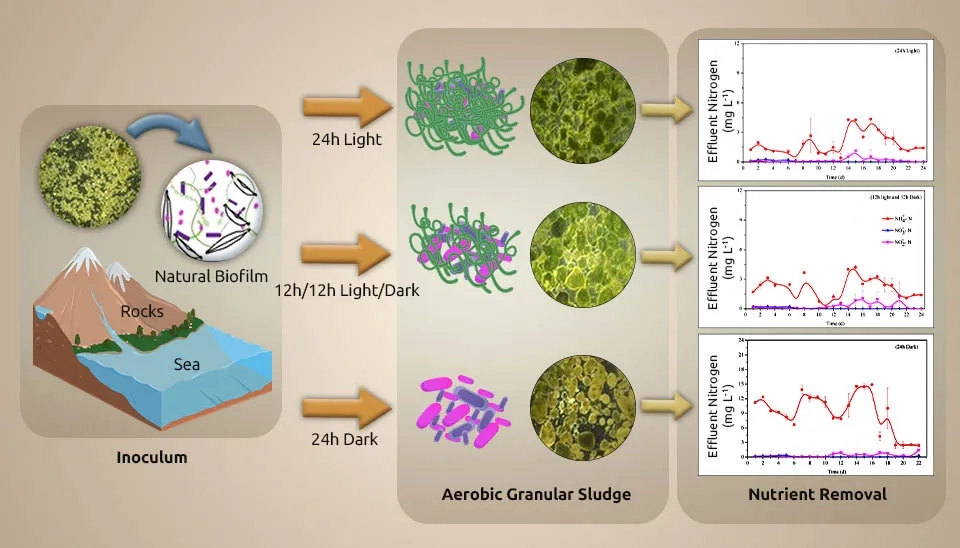

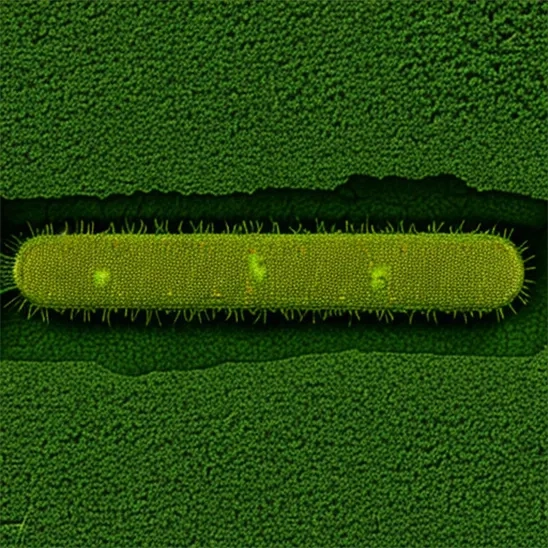

2.4. Microalgae (S. Obliquus) and Activated Sludge Bacteria (Nitrosomonas and Dechloromonas)

Purba et al. (2021) developed microalgae-bacteria aerobic granular sludge by a Photo-Sequencing Batch Reactor (PSBR) column (diameter of 6 cm and height of 100 cm). This study investigated the advancement of microalgae-bacteria aerobic high-impact granular sludge utilizing low-strength domestic wastewater. To develop MBC relations as aerobic granular sludge, use a mixture of Scenedesmus obliquus and AS at a ratio of 17% microalgae to 83% AS (v/v), respectively. A domestic wastewater sample was collected from the same local WWTP. The wastewater sample, on average, contained 189 mg L-1 COD, 26 mg L-1 TN, 24 mg L-1 ammoniacal nitrogen, and 6.2 mg L-1 TP. The volume exchange ratio (VER), cyclic time, and light intensity were 1.5 L (50% of VER), 3 hours, and 54 µmol m⁻²s⁻¹, respectively. Also, the flow rate of aeration, domestic wastewater volume, and reactor temperature were 2.5 L min-1, 750 mL, and 24 ± 3°C, respectively. Granular sludge was effectively created with the largest granule diameter of 6 mm within 30 days of the experimental period. The settling velocity and Sludge Volume Index (SVI30) of granules were obtained with 62.8 m h⁻¹ and 8 mL g⁻¹, respectively. Microalgae cells on the outer layer of granular sludge absorb well. The removal efficiency for removing COD and NH3-N was 72%.

2.5. Microalgae (C. Sorokiniana) and Bacteria (Nitrosomonas and Dechloromonas)

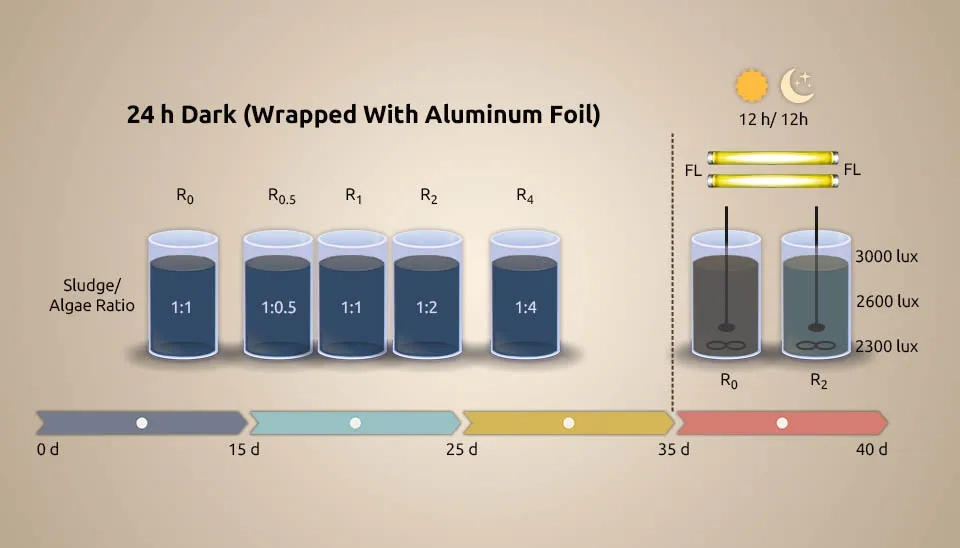

( Fan et al. 2019) systematically evaluated wastewater treatment by MBC, a Chlorella sorokiniana-activated sludge consortium, under dark heterotrophic conditions with a period of 12h/12h light/dark for the first time. Light limitation often occurs in the MBC. C. sorokiniana (10% (v/v)) was inoculated into 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 mL synthetic wastewater and improved for 3 days in an incubator under the following conditions: light intensity of 2000 lux, 12h/12h light/dark, 25°C, and shaking the flasks by hand 3 times/d. Activated sludge was collected from the aeration tank of the LBZ municipal WWTP in Wuhan, China. The activated sludge was cultured with synthetic wastewater in the lab, following cycles of anaerobic (2 h), aerobic (4 h), and settling (1 h), maintaining Mixed Liquid Suspended Solids (MLSS) at 2500 mg/L. The tests were done in wide-mouthed glass bottles with 1 L of synthetic wastewater at room temperature (25±2°C). The wastewater went through an anaerobic-aerobic cycle, which included feeding for 5 minutes, anaerobic for 2 hours, aerobic for 4 hours, settling for 1 hour, and decanting for 5 minutes. Microalgae and sludge depleted DO in manufactured wastewater after 7–15 minutes of magnetic stirring, and the anaerobic phase then continued to stir continuously at 120 rpm. We maintained DO, Solids Retention Time (SRT), and HRT at 2-4 mg L-1, 15 d, and 12 h, respectively. Chlorella sorokiniana grows in heterotrophic, autotrophic, and mixotrophic conditions. The sludge/microalgae ratio with ratios of 1:2 and 1:0 is introduced as R2 and R0. In the 1:2 ratio, nutrient (NH₄⁺-N and P) and COD removal efficiency were better than in the 1:0 ratio. Less O2 utilization of MBC than activated sludge made energy saving conceivable. Also, Fan et al. investigated interaction, which made the MBC ratio reversal 3:1. The ability of heterotrophic bacteria to handle glucose better than Chlorella sp., along with their interaction through substances like indole-3-acetic acid, siderophores, vitamins, and algicides released by bacteria, could explain why bacteria became more dominant in the MBC. Increased levels of cofactors and vitamins were the reason why microalgae and bacteria interacted more cooperatively. Secondary metabolites of terpenoids and polyketides were responsible for the less cooperative interaction between microalgae and bacteria. Despite oxidative stress within the dark consortium, microalgae photosynthesis reactivates when exchanged for light. The execution arrangement was light consortium > dark consortium > activated sludge. Nitrosomonas and Dechloromonas were improved for nutrient removal. The results show better removal efficiency of MBC over activated sludge, whether with or without light.

2.6. Microalgae (C. Sorokiniana DBWC2 and Chlorella sp.) and Bacteria (K. Pneumoniae ORWB1 and A. Calcoaceticus ORWB3)

The research by Goswami et al. (2019) looked into a long-term way to make crude oil by using hydrothermal liquefaction on microbial biomass that was made by growing microalgae and bacteria together and cleaning up wastewater. Four different types of wastewater samples were collected from the paper industry, the textile industry, the leather industry, and wastewater from effluent treatment plants. The total suspended particles of wastewater tests were settled down to dispense. The pH, total nitrogen, phosphorus, COD, and concentrations of two heavy metals—chromium and nickel—found in the wastewater were measured after the physical separation of the suspended particles was taken away. The wastewater tests were inoculated with 18% (v/v) inoculum, in which MBC was present in a ratio of 1:1 for 7 days. The wastewater tests were placed in an orbital shaker set to 150 rpm and maintained at 30 °C, exposed to a light intensity of 100 μE m−2 s−1 with a photoperiod of a 16:8 hour light-dark cycle, using 500 mL shake flasks. At the end of the incubation period, the wastewater samples were characterized and screened based on total biomass concentration and the removal efficiency of nutrients and heavy metals.

A tertiary consortium's biomass concentration and wastewater treatment efficiency of C. sorokiniana DBWC2, Chlorella sp., K. pneumoniae ORWB1, and A. calcoaceticus ORWB3 were assessed on four different wastewater tests. When the consortium was created using wastewater from the paper industry in a photobioreactor in group mode, the TN removal efficiency was found to be 3.17 g L−1, 99.95%, and the COD removal efficiency was determined to be 95.16%. Biomass concentration was improved to 4.1 g L−1 through discontinuous feeding of nitrogen and phosphate. The maximum distillate division of 30.62% lies inside the boiling point range of 200–300°C, indicating the suitability of the bio-crude oil for conversion into diesel oil, jet fuel, and stove fuel.

2.7. Microalgae (Chlorella sp.) and Bacteria (Bacillus Firmus and Beijerinckia Fluminensis)

Huo et al. (2020) investigated the co-culture of Chlorella and wastewater-borne bacteria in vinegar production wastewater. They looked at how well Chlorella and bacteria from wastewater (Bacillus firmus and Beijerinckia fluminensis) could remove nutrients and also how to collect Chlorella biomass, pigments, and lipids in vinegar production wastewater. Chlorella sp. grew in BG11 medium and was used with diluted water (1000 mL) to pre-cultivate the inoculum. The culture was set at 25 °C under a light intensity of 100 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹. We kept Chlorella sp. alive by mixing BG11 medium with increasing (10% to 100%) rates of vinegar-making wastewater. The process allowed the microalgae to continuously adapt to the high-acidity wastewater environment. Occasionally, the immunization of the microalgae for the treatment of vinegar wastewater and take-after-care considerations Chlorella sp. was grown in 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks that held 200 mL of the wastewater from the vinegar fermentation process. The flasks were kept at 26 °C and shaken continuously at 150 rpm while exposed to 50 ± 10 µmol m−2 s−1 of light. Chlorella sp. was inoculated into the medium with a normal initial cell concentration of around 1.0 × 105 cells/mL. After 24 hours of Chlorella sp. cultivation, the two bacteria underwent independent immunization at either 1% (v/v) or 10% (v/v) concentration into the medium.

The removal rates for COD, TN, and TP improved after adding the bacteria. At the end of the growth period, adding bacteria improved COD, TN, and TP removal rates by 22.1%, 20.0%, and 18.1%, respectively, compared to the group without bacteria. The average growth rates of Chlorella sp. in most groups decreased a little when grown with the bacteria. The bacteria Beijerinckia fluminensis found in wastewater effectively improved the pigment content of Chlorella sp. The chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoid concentrations were expanded by >35.7%, 20.9%, and 11.2%, respectively. This idea shows an effective co-culture system for microalgae and bacteria found in wastewater that could be used to make vinegar and treat wastewater. The recovery of high-value byproducts of microalgal pigment may balance the reduced amount of microalgae biomass.

2.8. C. Vulgaris MACC360: Native Bacteria from Sludge (Beer Brewing Factory)

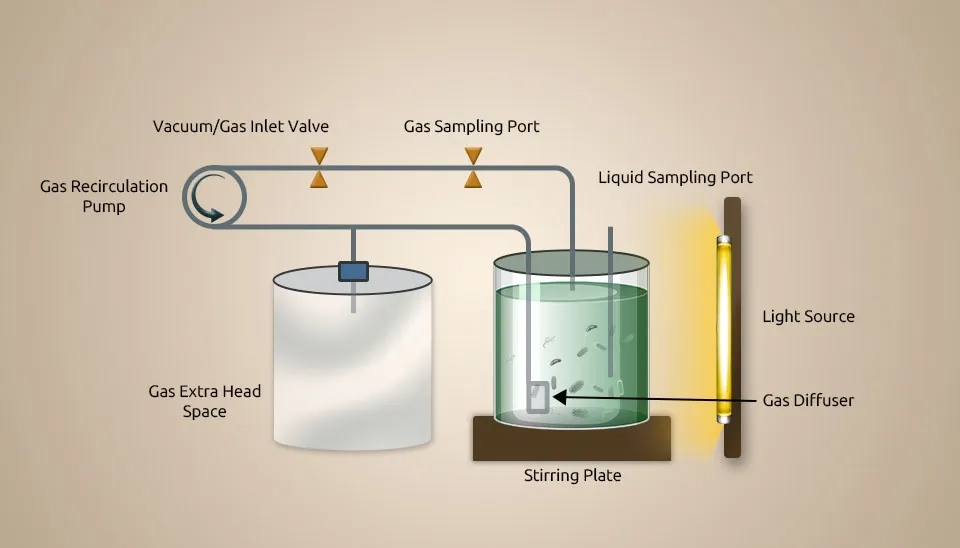

Shetty et al. (2019) investigated the exploitation of algal-bacterial consortia in combined biohydrogen generation and wastewater treatment. Their proposed approach applies green microalgae-based photoheterotrophic degradation using dark fermentation effluent as a substrate. Tests were done on a full-sized methane bioreactor filled with sludge from a brewery's wastewater pre-treatment process. The reactor was then kept at 32 °C for 24 hours. After that, the tests were held at 70°C for one hour to reduce the possible microorganisms that could use hydrogen, mostly methanogenic Archaea. The bacteria were connected as Enriched Microbial Inoculum (EMI), utilized in a 5% volume for photo-fermentation tests. Axenic microalgae Chlorella vulgaris MACC360 were included in the dark aging effluents for the photoheterotrophic degradation tests. The medium and plates were continuously incubated under 50 µmol m−2s−1 light intensity at 25°C.

The tests were done using 40 mL serum vials filled with 20 mL of dark fermentation liquid, which was treated with 2 mL of Ch. vulgaris (5.54 × 10 algae cells), and 1 mL (5%) of EMI was added for certain tests. Photoheterotrophic fermentation was performed at 24°C in batch mode for 72 h under continuous illumination with 50 µmol m−2s−1 light intensity, and the vials were shaken at 120 rpm.

EMI has around 10–20% biodegradation efficiency on the dark fermentation effluent compared to the microalgae, which is about 35–50%. The findings revealed that the quality of the relationships between the microbes and Chlorella affected how they could break down substances and produce biohydrogen. The study showed that the genetic makeup of the new system, which breaks down inorganic and organic compounds, makes microalgae very important for removing nitrogen and phosphorous. With more development and improvement, this new method can result in a very effective way to manage organic waste production and renewable energy production technology.

2.9. Microalgae (Coelastrella sp., Chlamydomonas sp., and Scenedesmus sp.a)

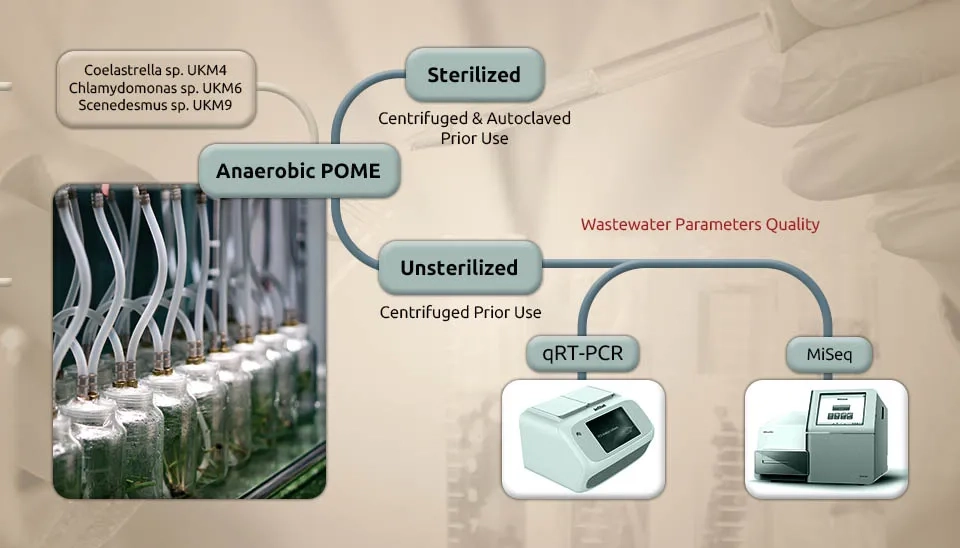

Udaiyappan et al. (2020) investigated the interaction of microalgae-bacteria in palm oil mill effluent treatment. The wastewater from a Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) was gathered from an anaerobic pond (anaerobic POME). POME contains considerable nutrients and a critical number of inborn microorganisms that devour the nutrients for their growth. The POME that wasn’t sterilized was pre-treated by centrifugation at 6800 g for 10 min to remove suspended solids and was kept at a temperature of 4°C until needed. The POME was autoclaved at 121°C for 15 minutes to prepare the sterilized POME. After the pre-treatment step, the POME was separated into fixed and unsterilized parts before use. Three native microalgae (Coelastrella sp., Chlamydomonas sp., and Scenedesmus sp.) isolates were used as a culture in this study. Around 10 % (v/v), 20 % (v/v), and 30 % (v/v) microalgae cultures at the exponential stage (dry cell weight ∼400 mg/L) were freely immunized into 2 L flasks containing unsterilized and sterilized POME, respectively. At that point, the cultures were hatched at room temperature with a continuous light supply at 10,000 lx and aeration at 0.25 vvm.

Carbon and nutrient contents are reduced in microalgae in the POME system. Three local types of microalgae, Coelastrella sp. UKM4, Chlamydomonas sp. UKM6, and Scenedesmus sp. UKM9, were grown in both cleaned and uncleaned anaerobic POME to study how they work together with bacteria to clean up POME. Due to the microalgae-bacteria consortia interaction, there is higher COD removal in unsterilized POME than in sterilized POME. The highest COD and PO4-3 removal percentages showed the interaction of Scenedesmus sp. UKM9 with bacteria is good. All three microalgae showed NH4+ removal of more than 80 % in both sterilized and unsterilized POME. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain response analysis showed that the amounts of bacteria were steady after the treatment, whereas the quantities of microalgae changed.

2.10. Microalgae (C. Sorokiniana) and Bacteria (M. Capsulatus)

Rasouli et al. (2018) looked into how to get nutrients back from industrial wastewater as single-cell proteins by growing green microalgae and methanotrophs together. They investigate the utilization of microalgae-bacteria symbiosis (MBS) to remove nutrients from industrial wastewater and upcycle them to produce single-cell proteins. Chlorella sorokiniana and Methylococcus capsulatus were acquired from microalgae and protozoa culture collections, respectively. Industrial wastewater (potato processing plant) was autoclaved, and solids were separated via centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Wastewater compositions containing COD, ammonium, and total phosphorus were 3000 mg L-1, 19 mg L-1, and 14 mg L-1. Before injection, 24-hour batch experiments were run with autoclaved wastewater to ensure that nonindigenous bacteria were active.

Results showed that Chlorella sorokiniana and Methylococcus capsulatus could remove or assimilate most organic carbon in the wastewater (~95% removal for the microalgae or bacteria and 91% for the MBC). Microalgae or bacteria growth stopped when carbon dioxide, methane, and oxygen for methanotrophs as nutrients and substrates in the gas phase were decreased. Chlorella sorokiniana development was likely light-limited and stopped after consuming organic carbon. Trace elements such as copper could limit the growth of methanotrophs. For all cultures, the protein content (45% of dry weight for methanotrophs, 52.5% of DW for microalgae, and 27.6% of DW for consortium) and amino acid profile were good enough to use instead of regular protein sources.

2.11. Microalgae (Chlorophyceae, C. Variabilis, P. Kessleri, P. Tricornutum, Chlamydomonas, and Synechocystis sp.) and Bacteria (T. elongatus, M. aeruginosa, Nostocales, Naviculales, Oscillatoriales, Stramenopiles, Trebouxiophyceae, Tricornutum, Chlamydomonas, Synechocystis sp., and Chroococcales)

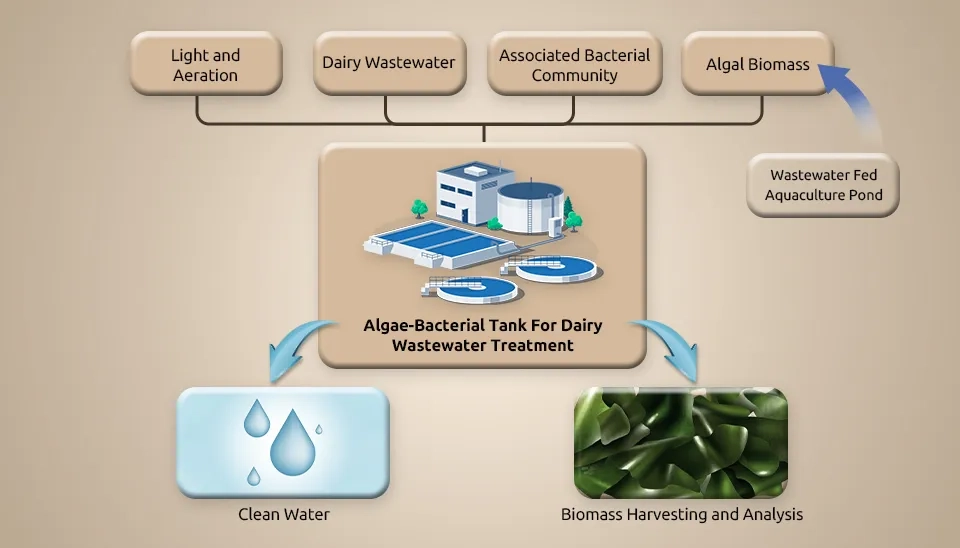

Biswas et al. (2021) investigated an eco-friendly strategy for dairy wastewater remediation with high lipid microalgae-bacterial biomass production using microalgae-bacterial consortia in wastewater treatment. They studied how to combine treatments to help with physical capacity and increase the production of lipids using a microalgae-bacterial consortium grown in a pond where wastewater from aquaculture is used as food. Biswas et al. collected microalgae samples from a pond in East Kolkata Wetland (EKW), Kolkata, India. They used clean bottles with caps to collect the samples and brought them to the laboratory at room temperature. The microalgae samples were placed on a clean surface with an algae agar medium and incubated at room temperature (25 ± 2°C) under light intensity (6309 lux) for about 14 days to grow. For bioreactor setup, 1 ml of the algal suspension was utilized as essential inoculum for cultivation in a rectangular glass aquarium (0.36 m × 0.12 m × 0.12m measurements given with 6309 lux) with a 2 L working volume. Every 48 hours, 50% of the suspension arrangement in the tank was replaced with new media, such as diluted dairy wastewater or Whatman-filtered Bheri water. This process continued for up to 15 days to stabilize the consortium in the tanks.

The microalgae used were Chlorophyceae, Chlorella variabilis, Parachlorella kessleri, Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Chlamydomonas, and Synechocystis sp., while the bacteria included Thermosynechococcus elongatus, Oscillatoriales, Microcystis aeruginosa, Nostocales, Naviculales, Stramenopiles, Trebouxiophyceae, and Chroococcales, which could help clean up the environment. Amid a 30-day trial run (15 days of stabilization and 14 days of remediation studies) for phytoremediation, an extreme decrease in the nutrient and COD substances from the tested wastewater tests was seen. COD and ammonium concentrations were reduced to 93% and 87.2%, respectively. Also, for all seven cycles, nearly 100% of nitrates and phosphates were removed from the dairy wastewater after 48 hours of treatment with polyculture at a surrounding temperature of 25 ± 2 °C, with 6309 lux lighting and gentle aeration and COD concentrations within the treated water were below the release standards, as per Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) standards. In expansion, dry cell weight was improved by 67% upon treatment with ammonia-rich dairy wastewater, showing a 42% lipid, 55% carbohydrate, and 18.6% protein content upgrade.

2.12. Microalgae (C. Sorokiniana DBWC2 and Chlorella sp. DBWC7) and Bacteria (K. Pneumoniae ORWB1 and A. Cacoaceticus ORWB3)

Makut et al. (2019) investigated the production of microbial biomass feedstock via co-cultivation of a microalgae-bacteria consortium coupled with effective wastewater treatment. They demonstrated the microalgae-bacteria consortium as a sustainable process for producing biomass feedstock associated with wastewater treatment. The types of microalgal and bacterial strains were isolated from oil refinery wastewater. The microalgae was grown in BG11 medium and incubated in an orbital shaker at 150 rpm and 30 °C beneath 100 μE m−2s−1 light intensity with a light-dark cycle of 16:8 h.

The most effective combination microalgae-bacteria consortium was made up of two types of microalgae, Chlorella sorokiniana (DBWC2) & Chlorella sp. (DBWC7), and two types of bacteria known as Klebsiella pneumoniae (ORWB1) and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (ORWB3). The consortium tested the microalgae and bacteria group with both synthetic and raw dairy wastewater. Using microalgae and bacteria together made the microalgae grow much faster, remove more COD, and do a better job of removing nitrates than using the algae alone. Total biomass titer, nitrate removal, and COD removal efficiency were found to be 2.84 g L-1, 93.59%, and 82.27%, and 2.87 g L-1, 84.69%, and 90.49% in counterfeit wastewater and crude dairy wastewater, respectively. The chosen microalgae-bacteria consortium is a promising method for economically generating microbial biomass utilizing wastewater.

2.13. Microalgae (C. Vulgaris) and Bacteria (R. Sphaeroides)

You et al. (2021) investigated upgrading nutrient recovery from wastewater, nitrogen-rich piggery wastewater (PW), and carbon-rich starch wastewater (SW) treated using photosynthetic microorganisms. PW and SW were collected from a pig farm and a local bakery in Nanchang, China. The filter cloth filtered PW with a diameter of 50 μm to remove the particulates. PW and SW are assumed to be perfect media for developing microorganisms due to their abundant nutrients (e.g., nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) and other essential trace components (e.g., magnesium and iron). The results showed that the recuperation efficiencies of nutrients in PW and SW treated through the cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris and Rhodobacter sphaeroides, respectively, were moderately low. C. vulgaris seems not to grow on SW. Co-culturing C. vulgaris and R. sphaeroides significantly improved the recuperation execution of the PW and SW blend. By co-culturing C. vulgaris and R. sphaeroides, it was possible to create microalgae-bacteria consortia. The mixture of PW and SW took 100%, 96%, 97%, and 95% longer to recover NH4+-N, TP, COD, and TN when C. vulgaris and R. sphaeroides were grown together. Carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins were the three primary fixings within the biomass of photosynthetic microorganisms.

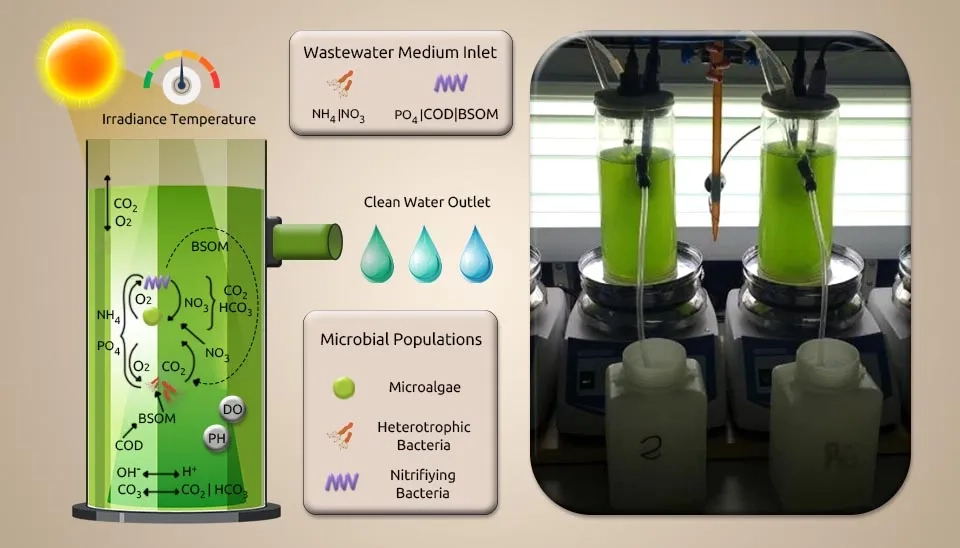

Sánchez-Zurano et al. (2021) investigated a new model of microalgae-bacteria consortia for biological treatment of wastewaters named A Microalgae-Bacteria Consortia (ABACO). Scenedesmus Almeriensis was used to inoculate the photobioreactors, which were maintained photoautotrophically in spherical flasks with a volume of 1 L using the Arnon medium. Other conditions were artificially illuminated, such as CO₂-enriched air (1%), pH (8.0), temperature (25°C), a 12:12 h L/D cycle, and light intensity of 750 µE m⁻² for the tests. 20% Scenedesmus Almeriensis and 20% diluted pig slurry were put into two photobioreactors made by hand out of polymethyl methacrylate. The reactors were 0.08 m in diameter, 0.2 m in height, and could hold 1 L.

The ABACO model incorporates the most significant highlights of microalgae, such as light reliance, endogenous respiration, and development and nutrient utilization as a function of nutrient availability (especially inorganic carbon (IC)), in addition to the as-of-now detailed features of heterotrophic and nitrifying bacteria. Genetic algorithms have calibrated the model parameters in MATLAB software. The ABACO model lets you simulate the movements of different parts, such as the amounts of microalgae, heterotrophic bacteria, and nitrifying bacteria. The ABACO model uses respirometry techniques to determine the percentage of each microbial population obtained. This ABACO model is a vital tool for improving how we treat wastewater with microalgae. It helps us increase microalgal biomass production and optimize wastewater treatment effectively.

2.15. Microalgae (C. Vulgaris) and Bacteria (Nitrosomonas)

Okurowska et al. (2021) investigated adapting the algal microbiome for growth on domestic landfill leachate. They aimed to enhance the growth rate of Chlorella vulgaris on leachate by optimizing the MBC system. One liter of landfill leachate was collected from a leachate lake in a sterile glass holder. When the leachate arrived at the lab, 10 mL was mixed with Bold's Basal Medium (BBM) to make 100 mL. This sample was then put into 250 mL flasks with cellulose plugs to allow gas exchange. The flasks were then kept at 25 °C with shaking at 150 rpm and a light intensity of 40 μE m−2 s−1, with a 12:12 h L/D cycle. The microalgae-bacterial consortia in wastewater treatment were subsequently subcultured into fresh BBM with 10% (v/v) leachate at a ratio of 1:10. Finally, the culture medium was incubated for 21 days at 25 °C with shaking at 150 rpm under a light intensity of 40 μE m−2 s−1, 12:12 h L/D cycle.

Chlorella vulgaris grows faster in groups of microalgae and bacteria, and the growth rate is sped up by almost three times to 0.2 d−1. Nitrosomonas numbers were not detected in the microalgae-bacterial consortium and NO3--N was reduced because microalgae utilized NH4+-N. The pathways known to be involved in the microalgae-bacterial consortia in wastewater treatment, including degradation of aromatic compounds, benzoate, and naphthalene, predicted metagenomic functional content by Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt).

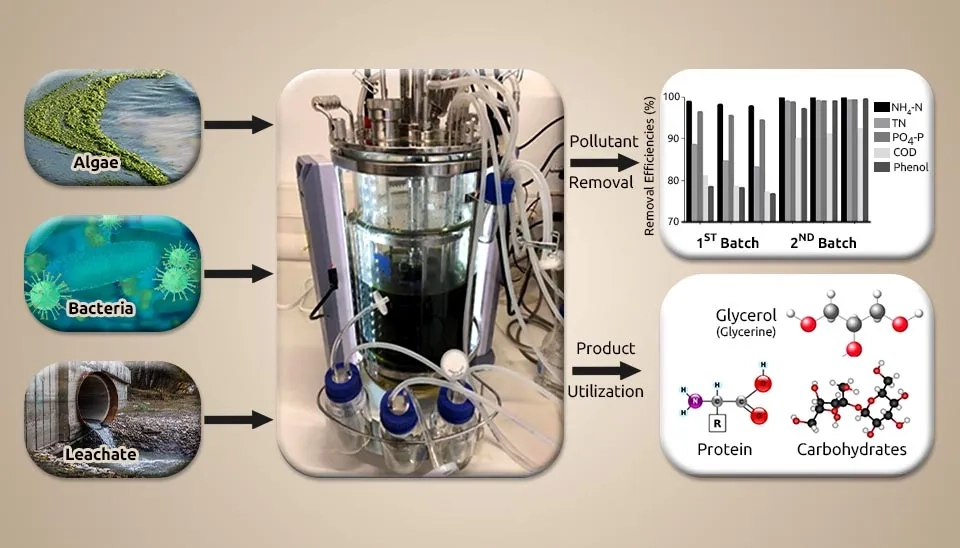

2.16. Microalgae (Chlorella sp., Scenesdesmus sp., Stigeoclonium sp.) and Cyanobacteria (Microcystis sp., Oscillatoria sp.)

Tighiri and Erkurt (2019) investigated the biotreatment of landfill leachate by a microalgae-bacteria consortium in sequencing batch mode. The coexistence of microalgae and bacteria played an imperative role in leachate treatment and biomass generation for biorefinery purposes. Microalgae strains (Chlorella sp., Scenesdesmus sp., Stigeoclonium sp.) and Cyanobacteria (Microcystis sp., Oscillatoria ssp.) were taken from the aerobic oxidation section of the wastewater treatment plant in Nicosia, examined under a microscope, and then grown in BG11 medium for 14 days in a photobioreactor with a light intensity of 76 μmol m-2s-1 and a speed of 75 rpm at 28°C. The tests were conducted in a photobioreactor with a 10 L volume and 5 L loading with 10% (v/v) diluted landfill leachate in a sequencing batch. The pH, temperature, and DO were automatically maintained within a range of 6.5–8.5, 25 ± 1°C, and 5.0–8.0 mg L⁻¹, respectively. The starting biomass of bacteria and microalgae was kept at a 3:1 ratio for all cycles. We took this action to boost the microalgae biomass and prevent the bacteria from dominating the MBC system for biorefinery purposes. Microalgae and bacteria initial concentrations were 0.343 g L-1 and 0.115 g L-1 for cycle I, 0.339 g L-1 and 0.112 g L-1 for cycle II, and 0.354 g L-1 and 0.117 g L-1 for cycle III, respectively. The initial biomass concentration was improved to start the second batch, which consists of three consecutive cycles. The biomass concentration of microalgae and bacteria increased to 1.338 g L-1 and 0.439 g L-1 for cycle I, 1.341 and 0.446 gL-1 for cycle II, and 1.364 g L-1 and 0.455 g L-1 for cycle III, respectively. NH4+-N was wholly removed from the leachate in both batches. NO3-, COD and phenol removal efficiencies were above 90% in the 2nd batch. At the end of the second batch, the relative toxicity had reduced from 57.32 to 1.12%. The fatty acid content (C16:18) rose from 86.72 to 87.69% in the second batch and fell from 85.47 to 87.65% in the first batch. Also, in the 1st batch, the crude glycerol content increased from 34.54 to 42.36%, and in the 2nd batch, from 33.64 to 39.55%.

2.17. Microalgae (C. Pyrenoidosa) and Bacteria (Nitrogen Fixation)

Nair and Nagendra (2018) investigated the phytoremediation of landfill leachate by Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Chlorella pyrenoidosa was initially cultivated in BBM. Landfill leachate and municipal wastewater were collected from the landfill and the inlet chamber of the sewage treatment plant located within the institute campus in Chennai, India, respectively. Due to removing any large-size solids, the leachate and sewage were screened through a coarse filter and kept at 4°C. The supernatant was filtered through the Whatman paper and siphoned off before being utilized as microalgae culture media. The microalgae culture was agitated in an incubator at 100 rpm and placed in an enclosed chamber illuminated with a light intensity of 8000 lux. Landfill leachate was mixed with municipal sewage in different proportions (10–50%). C. pyrenoidosa subcultured in BBM was added with 5% sterilized landfill leachate until it adapted to landfill leachate. Microalgae biomass was defined by gathering 1 mL of suspension and centrifuging at 5000g for 10 min. The supernatant was rejected, and the pellets were dried at 60°C for 24 hours. All tests related to phytoremediation were performed at an ambient temperature of 26 ± 2°C. The C. pyrenoidosa was protected during the phytoremediation process from a group of bacteria that fix nitrogen in landfill leachate and city wastewater. The batch-scale study was scaled up to a 3-liter tubular PBR. The PBR's outer diameter and height (of Plexiglas with a work volume of 2000 mL) were 90 mm and 600 mm, respectively. Aeration was done to the bottom (1.0 L min⁻¹) to ensure suitable blending in the PBR. The results indicated that C. pyrenoidosa could develop in an arrangement containing up to 30% landfill leachate spiked in sewage. The phytoremediation process was further scaled up to treat a 30% landfill leachate-spiked solution in a laboratory-scale photobioreactor. In the biomass concentration of C. pyrenoidosa 2.8 g L-1, DOC, TN, and orthophosphate removal obtained 81, 70, and 89% in the phytoremediation process.

2.18. Microalgae (Chlorella vulgaris NIES-227) and Bacteria (Proteobacteria, Planctomycetes, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Nitrospirae, Actinobacteria)

Feng et al. (2020) investigated the performance of a microalgal-bacterial consortium system for treating dairy-derived liquid digest and biomass production. They introduced a new microalgal-bacterial consortium system (co-culture) to enhance Dairy-derived Liquid Digestate (DLD) treatment using a microalgal-bacterial consortium system composed of Chlorella vulgaris and indigenous bacteria, activated sludge. Before the experiment, the liquid digestate collected from a dairy farm in Kaiping (China) was centrifuged and filtered by Whatman glass microfiber filters to remove large particles and stored in a 4°C refrigerator until further use. The liquid digestate had to be diluted due to the significant inhibition of microalgae cell growth. Due to the considerable inhibition of algal cell growth in the raw liquid digestate, it had to be diluted. The ideal alternative medium was 25% DLD for biofuel generation and nutrient removal. The concentrations of COD, TN, NH4 +-N, and TP in the 4 times diluted liquid digestates were 390 ± 1, 162 ± 1, 135.5 ± 0.5, and 20.23 ± 0.07 mg L-1, respectively. Chlorella vulgaris NIES-227 was kept in BG-11 medium and pre-cultured in an air-lift Photo Bio Reactor (PBR) with a 5.0 cm diameter and 60 cm height at room temperature and a light intensity of 200 μmol m−2 s−1 with 24 hours of illumination. Aeration was done at 0.3 vvm with 2% CO2-enriched air at the bottom of the PBR. Pre-cultured microalgae cells were gathered to adapt to the liquid digestate medium and add to the log phase. For C. vulgaris, acclimation was consecutively cultivated on digestate concentrations of 5%, 15%, and 25% in PBR within a semi-continuous growth method. Half the volume of the culture was raised, and freshly diluted digested liquid was added to the culture in the log phase. Finally, C. vulgaris was maintained at 25% digestibility and utilized for further tests. All tests were applied in the PBRs using four times diluted liquid digestate as wastewater. The initial concentration of C. vulgaris was about 0.5 g L⁻¹. The addition of activated sludge in the culture increased the specific growth rate of C. vulgaris by about 0.56 d⁻¹ due to the shortened lag phase. The biomass yield in C. vulgaris (3.24 g L⁻¹) was higher than in the co-culture (2.72 g L⁻¹), but COD removal of the co-culture (25.26%) was higher than in C. vulgaris (13.59%). Metagenomic and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analyses showed that C. vulgaris also improved bacterial growth but unexpectedly affected the bacterial communities of indigenous bacteria and activated sludge. Activated sludge was a more desirable symbiosis with C. vulgaris than indigenous bacteria. These results confirmed the manufacturing of an effective microalgal-bacterial consortium system for wastewater treatment.

2.19. Microalgae (Chlorophyceae sp.) and Bacteria (Alphaproteobacteria and Sphingobacteria)

Ji et al. (2021) investigated microalgal-bacterial granular sludge under simulated natural cycles for municipal wastewater treatment. They used Microalgal-Bacterial Granular Sludge (MBGS) in synthetic wastewater under aerobic and non-aeration conditions in a 250 mL glass beaker. The dominant microalgae and bacteria (Chlorophyceae, Alphaproteobacteria, and Sphingobacteriia) were identified in MBGS. The average size and 5-min Sludge Volume Index (SVI5) of MBGS were 0.72 mm and 22.3 mL/g, respectively. Tests were conducted in glass reactors with a 60-mL volume, a temperature of 25°C, and a shaking speed of 150 rpm min⁻¹ under a 12:12 D/L cycle. Carbon sources in this study were acetate, glucose, and sucrose. The DO concentration was 4–5 mg L⁻¹ and 5–8 mg L⁻¹ in the dark and light phases. Also, HRTs were 2 h and 4 h in light and dark stages, respectively. The initial MBGS concentration and illumination intensity were set to be 14 g L⁻¹ of volatile suspended solids (VSS) and 200 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹. In the daytime (HRT of 2), there were about 94.9% of organics, 69.5% of NH4+-N, and 90.6% of PO4-3-P, and during the nighttime (HRT of 4 h), there were 93.1% of organics, 62.5% of NH4+-N and 80.8% of PO4-3-P. Chlorophyceae were found to be the main ones that got rid of the phosphorus because they have H+-exporting adenosine triphosphate (ATPase) and H+-transporting two-sector ATPase. Also, the main ones responsible for the ammonia removal were found in Alphaproteobacteria due to glutamine synthetase and glutamate dehydrogenase.

2.20. Microalgae (C. Vulgaris) and Bacteria (Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Deferribacteres, Comamonadaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, Chitinophagaceae, and Xanthomonadaceae)

Hassan et al. (2019) investigated the biomonitoring detoxification efficiency of an algal-bacterial microcosm system to treat coking wastewater. Coking Waste Water (CWW) has harmful, mutative, and carcinogenic components with undermining environmental impacts. A bioreactor that is 30 cm wide, 25 cm long, and 20 cm high, with a working volume of 9 L, was used to watch how the microalgae and bacteria system changed to treat wastewater from an Egyptian coal coking factory. We worked on the PBR for 154 days, adjusting specific parameters (harmful load and light term) for optimization. Optimized conditions accomplished a critical decrease (45%) in the operation cost. The PBR initially used the MBC with Mineral Salt Medium (MSM). We inoculated the PBR with 10% (v/v) of Chlorella vulgaris MM1 and a real wastewater mixture in a 5:1 ratio. Temperature, light intensity, agitation, and HRT during processing were 25 ± 2°C, 5000 ± 500 lux, 140 rpm, and 3 days with a 1 h ON/2 h OFF cycle, respectively. The MBC was observed utilizing chemical tests and bioassays such as phytotoxicity, Artemia toxicity, cytotoxicity, algal-bacterial ratio, settleability, and Illumina-MiSeq sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene. Tests of 300 ml were drawn on a day-by-day basis and subjected to the following analytical regimen: pH, DO, temperature, optical density (OD600nm), bacterial viable count, algal chlorophyll content, algal/bacterial ratio, COD, and phenol concentration. The MBC was used to detoxify phytotoxicity, cytotoxicity, and Artemia toxicity. Throughout all phases, we introduced CWW as an influential factor. The microbial sample diversity between influent and effluent was significant. Four phyla, Proteobacteria (77%), Firmicutes (11%), Bacteroidetes (5%), and Deferribacteres (3%), showed up in influent samples and Proteobacteria (66%) and Bacteroidetes (26%) were indicated in effluent samples. The critical relative plenitude of versatile aromatic degraders (Comamonadaceae and Pseudomonadaceae families) in influent tests acclimated to the nature of CWW. The microbial community moved and advanced the action of metabolically flexible and xenobiotic-degrading families such as Chitinophagaceae and Xanthomonadaceae. Co-culture of microalgae positively impacted the biodegrading bacteria by improving treatment effectiveness, significantly increasing the relative wealth of bacterial genera with cyanide-decomposition potential, and negatively impacting waterborne pathogens.

2.21. Microalgae (Desmodesmus or Scenedesmus Dominant) and Bacteria (Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes)

Carney et al. (2014) investigated microbiome analysis of a microalgal mass culture growing in municipal wastewater in a prototype Offshore Membrane Enclosures for Growing Algae (OMEGA) photobioreactor at the Southeast Wastewater Treatment Plant in San Francisco. Large-scale microalgae cultivation for biofuels may maintain a strategic distance from competing for agriculture, water, and fertilizer by utilizing wastewater and avoiding competition for land using the OMEGA system. The wastewater was 1600 L circulating at 10 cm s−1 through four floating PBR tubes (0.2 m × 9.1 m) made of translucent 0.38 mm linear low-density polyethylene with a nylon center. To eliminate contaminating microorganisms, it was frequently flushed with “#2 water,” which is sand-filtered Final Plant Effluent (FPE) treated with sodium hypochlorite (4–8 mg L−1), maintaining a chlorine residual of 4 mg L−1 for 12 h. The system was refilled with #2 water, and the hypochlorite was neutralized with equimolar sodium metabisulfite. Nutrient concentrations were NH₄⁺-N 41.3 ± 1.7 mg L−1; NO3--N 0.45 ± 0.3 mg L−1; PO4-3−3.0 ± 0.7 mg L−1 for the #2 water and the FPE were comparable on the day of inoculation. Stock cultures of mixed Scenedesmus sp. and Desmodesmus sp. were maintained in BG-11 medium with 150 L volume in a room-temperature, lighted incubator (61 μmol m−2 s−1) with shaking at pH 7.6–8.2. The OMEGA system was inoculated to a cell density of ~2.3 × 107 cells mL⁻¹ with OD750nm 0.34 and Total Suspended Solids (TSS) 0.124 g L⁻¹. The observed bacteria, at first dominated by γ-proteobacteria, moved to Cytophagia, Flavobacteriia, and Sphingobacteriia after the expansion of exogenous nutrients. The overwhelming algae genera presented with the inoculum, Desmodesmus and Scenedesmus, remained over 70% of the grouping peruses on day 13, despite the OD and fluorescence of the culture declining. Nonalgal Eukarya, overwhelmed by unclassified alveolates, cryophytes, and heliozoan grazers, moved to chytrid fungi on day 5 and proceeded to day 13.

2.22. Microalgae (Scenedesmus Dominant) and Bacteria (Proteobacteria, Bacteroides)

Krustok et al. (2015) looked into how lake water changed the number of algae and the microbial community structure in lab-scale photobioreactors that were based on wastewater from cities. Photobioreactors with a work volume of 20 L were set up and ran for 16 days. The ratio of wastewater to tap water as a medium was 70:30 in PBR for microorganism growth. Also, in the second stage, the wastewater and lake water ratio (70:30) was applied based on the results of an earlier small-scale pilot study. The PBR was implemented with gentle stirring at around 270 rpm, aeration of 3 L/min, a light intensity of 135 μmol m⁻²s⁻¹, a temperature of 23±0.5 °C, and 16/24 light/dark cycle conditions. The metagenome-based overview showed that the foremost inexhaustible microalgae phylum in these reactors was Chlorophyta, with Scenedesmus being the foremost unmistakable genus. The most tenacious bacterial species were Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes, with the central prevailing families being Sphingobacteriaceae, Cytophagaceae, Flavobacteriaceae, Comamonadaceae, Planctomycetaceae, Nocardiaceae and Nostocaceae. PBRs were effective at reducing the overall number of pathogens in wastewater compared to reactors with a wastewater/tap water mixture. Proper investigation of the photobioreactor metagenomes uncovered an increase in the relative wealth of genes related to photosynthesis and synthesis of vitamins imperative for auxotrophic algae and a decrease in destructiveness and nitrogen digestion subsystems in lake water reactors. The study results show that including lake water in the wastewater-based photobioreactor leads to a modified bacterial community phylogenetic and valuable structure that can be connected to higher algal biomass generation and improved nutrient and pathogen reduction in these reactors.

2.23. Microalgae (Chlorella Vulgaris and Pseudanabaena dominante) and Bacteria (Proteobacteria)

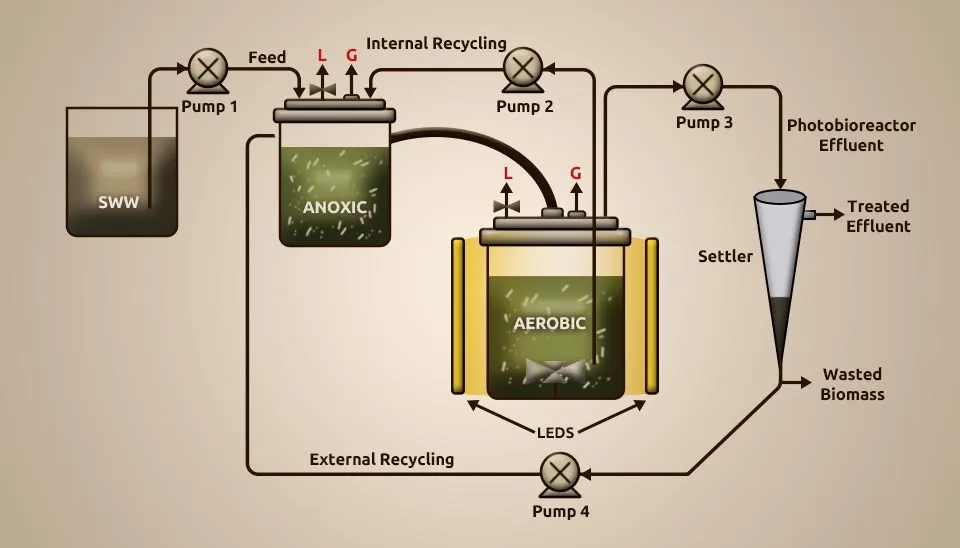

Alcántara et al. (2015) studied how well a new anoxic-aerobic algal-bacterial photobioreactor cleaned up wastewater by looking at carbon and nitrogen mass balances and biomass recycling. The anoxic and aerobic tanks were first filled with 3.2 grams per liter of total suspended solids (TSS) made up of bacteria and microalgae from wastewater treatment using High-Rate Algal Ponds (HRAP) that processed diluted vinasse and aerobic activated sludge from the Valladolid wastewater treatment plant. The MBC utilized as immunization was first settled, and the biomass was resuspended in synthetic wastewater (SWW) prior to inoculation in both reactors. The dissolved Total Organic Carbon (TOC), dissolved IC, and N-NH4+ were 200 mg L-1, 250 mg L-1, and 120 mg L-1, respectively. The experimental setup comprised an anoxic tank interconnected to a PBR. The PBR was an encased 3.5-L glass tank with a total working volume of 2.7 L. The PBR was continuously under light intensity 400±51 µE m⁻² s⁻¹, temperature 24±1 °C, magnetic agitation 300 rpm, and pH 7.8±0.1. The anoxic reactor comprised a gas-tight L polyvinyl chloride tank with a total working volume of 0.9 L kept in the dark and magnetically blended at 300 rpm. The SWW, already sterilized at 121ºC for 20 min and kept up at 7ºC, was nourished in the anoxic tank and continuously overflowed by gravity into the aerobic photobioreactor. The MBC was continuously recycled at 3 L d⁻¹ from the PBR to the anoxic tank to provide the NO2 and NO3 required for denitrification. A 1L Imhoff cone interconnected to the PBR outlet was used as a settler. The algal-bacterial biomass settled was reused from the foot of the pioneer into the anoxic tank at 0.5 L/d and squandered three days a week to control the algal-bacterial SRT. We used a creative anoxic-aerobic photobioreactor setup to reuse the biomass. This process effectively removed TOC (86–90%), IC (57–98%), and TN (68–79%) during SSW treatment, with hydraulic retention time of 2 days and sludge retention time of 20 days. How easily IC got into the PBR from the wastewater and how active the microalgae were showed how much nitrogen was taken out by absorption or nitrification-denitrification. Nitrate generation was unimportant despite the high DO concentrations; denitrification was based on nitrite reduction. Using recycled biomass increased the amount of quickly settling algal flocs, which kept the TSS levels in the effluent below the maximum release limits set by the European Union. Lastly, the highest levels of nitrous oxide emissions were much lower than those found in wastewater treatment plants. Results show that this PBR can be kept up without causing global warming problems.

2.24. Microalgae (Picochlorum sp.) and Bacteria (Proteobacteria)

In 2015, Babatsouli et al. looked into how marine bacterial-microalgae consortia could treat salty wastewater in a fixed-bed photobioreactor in a single step. AdvanTex is depicted as an upgraded PBR treatment process. “AdvanTex” is a commercial name for an immobilized or packed bed bioreactor. AdvanTex provides dependable wastewater treatment amid “peak flow” conditions. Its employment as a synthetic textile as the bolster medium for microbes, based on the attached growth process, was examined for the first time in treating saline wastewater. Destinations ranging from single-family homes to community systems could utilize this compact system. The more advanced version of this technology combines dosing, spreading evenly, and replacing the granular medium with a textile medium made of polypropylene synthetic fiber, which is solid and safe for biodegradation. AdvanTex has many benefits, including higher porosity, a large total surface area per unit volume, and a high water-holding capacity. These properties help the biomass grow and collect solids, making it easier for air and wastewater to contact it. This, along with the changed dosing time, controls the wastewater maintenance time inside the filter, affecting the effluent's quality. The AdvanTex Treatment Process could be a recycling process in which wastewater enters the recirculation-feed tank, and a timer-controlled pump running many hours a day occasionally measures wastewater to a dissemination system on the best of the AdvanTex filter media. The optimum pump operation time is 2 minutes on and 8 minutes off, with an ample pump operation time of 4.8 hours daily. Each time the filter is dosed, effluent gradually permeates through and between the textile sheets, where it is treated by the microbial community that populates the filter in a wet, oxygen-rich environment. After passing through the filter media, the treated effluent streams out of the filter unit through a return line that transports the effluent to the distribution tank. The treated effluent is recycled to the distribution tank after 3–4 minutes. A new group of microbes, including Chitrinomycetes and Pseudomonas species, grew on the fabric after being inoculated with Picochlorum sp. Nutrient removal rates of up to 95% were obtained within a few hours (4-5 h) of operation in PBR. These results are supported by evidence from a quantitative polymerase chain reaction. This evidence shows that heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification are the main ways N leaves the bioreactor.

2.25. Microalgae (Chlorella sp. Dominant) and Bacteria (Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes)

Ye et al. (2016) studied how the structure of microbiota changes during the process of cleaning swine lagoon wastewater, which has high levels of organic carbon, ammonium (N), and phosphorus (P), in Chongming, Shanghai, China. After collection, the wastewater was pre-settled overnight to remove massive particles, whereas the inborn microflora was held without sanitization treatment. The characteristics of the wastewater were characterized as follows: pH, 7.8; COD, 323 ± 21 mg L-1; NH3–N, 49.1 ± 3.0 mg L-1; NO3–N, 2.4 ± 1.1 mg L-1; and TP, 4.5 ± 1.2 mg L-1. Culture media, temperature, working volume, CO2 (v/v), the airflow rate, the shaking flasks, and light intensity were BG11, 25 ± 2 °C, 300 mL, 1%, 0.2 vvm, 150 rpm, and 100 μmol m-2s-1, respectively. The three setups for treating lagoon wastewater were (1) control with no vaccination of exogenous microorganisms within the shaking flasks, (2) inoculation of Chlorella sp. within the wastewater in the shaking flasks, and (3) immunization of Chlorella sp. within the wastewater within the CO2-air lift columns, with the two treatments getting microalgae biomass immunization at a level of around 0.1 g L-1. The results showed that the immunization of microalgae can significantly enhance N and P removal. In differentiation within the CO₂-air bubbling system, a specialty for more mutualistic bacteria was made, which resulted in maximal algal development with concurrent optimal N and P removal.

2.26. Microalgae (Auxenochlorella Protothecoides UTEX 2341 and C. Sorokiniana UTEX 2805 ) and Bacteria (Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes)

Higgins et al. (2018) investigated algal-bacterial synergy in the treatment of winery wastewater exiting the oxidation tank from a treatment plant located at a large winery in California. To remove large particulates from sterile wastewater, the water was first passed through a 0.45 μm filter and then through a 0.2 μm filter to remove bacteria. The non-axenic cultures directly used the thawed wastewater without any filtering. UTEX 2341 and UTEX 2805 of Auxenochlorella Protothecoides overgrew and eliminated more than 90% of the NH3-N and more than 50% of the PO4-3 in wastewater. They also got rid of all of the acetic acid. Auxenochlorella Protothecoides were grown on N8-NH4 medium (in cell density OD550 of 0.2), and cell dry weight was 0.11 g/L. Also, the cell dry weight of C. sorokiniana in the N8 medium reached 0.13 g/L. It has been shown that pre-cultures can grow with 400 mL min-1 of sterile-filtered 2% CO2 mixed with air at a rate of 125 mL min-1 and 10,000 lux of light on a 16:8 L/D cycle. Both algae strains develop faster on wastewater than on minimal media. Organic carbon within the wastewater played a constrained part in improving microalgae development. A. Protothecoides enhanced soluble COD loadings in two wastewaters, and C. sorokiniana secreted an insoluble film. Refined microalgae in the local wastewater microbial community nullified the emission of algal photosynthate, permitting concurrent diminishments in COD and nutrient concentrations. Both microalgae species invigorated bacterial growth in a strain-specific way, proposing particular reactions to algal photosynthate. Cofactor autotrophy for thiamine, cobalamin, and biotin is far-reaching among algae, and these cofactors are regularly obtained from bacteria. Sequencing the wastewater microbial community uncovered bacteria competent in synthesizing all three cofactors. In contrast, liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry (LCMS) and bioassays revealed the presence of thiamine metabolites within the wastewater. These cofactors likely expanded algal growth rates, especially for A. Protothecoides, which cannot synthesize thiamine de novo but can rescue it from corruption. Collectively, these results illustrate that the combination of bacteria and microalgae in wastewater treatment has synergistic growth benefits, possibly contributing to higher levels of wastewater treatment than either organism type alone (Higgins et al. 2018).

3. Conclusion

This review highlights the potential of the microalgae-bacteria consortium for wastewater treatment and nutrient (N, P) removal. The survey solidifies the current understanding of microalgae characteristics and their interactions with bacteria in a consortium system. Microalgae-bacteria consortium (MBC) systems can flourish in various conditions and are associated in different ways, from mutualism to parasitism. This review compares recent developments in the practical application of pure and consortium systems in other wastewater treatments (domestic, industrial, agro-industrial, and landfill leachate wastewater). It highlights an MBC system's capacity to utilize sewage nutrients and create profitable microalgae-based items. This review also discusses the potential of wastewater-derived microalgal biomass as a promising feedstock for animal feed, biofertilizers, biofuel, and numerous essential biochemicals. The main area that needs more research in microalgae WW treatment is genetic studies that look into the specific mechanisms that help some microalgae strains survive in WWs with many nutrients and pollutants. Transcriptomics and proteomics studies uncover that toxins and harsh WW conditions inspire a cellular stress reaction comparable to most natural stresses. Photosynthesis is the foremost influence on cellular physiology, while oxidative stress is the most common reaction to the presentation of contaminants such as HMs. Analysis of different qualities of genes and proteins. In contrast, studies must comprehend the qualities of genes and proteins. While omics analysis will give us essential information about how microalgae live and break down waste in wastewater, the fact that there are not many pilot-scale microalgae wastewater treatment plants that work well shows that this kind of system is possible. Wastewater treatment by MBC must overcome all the obstacles in microalgae and bacteria technology, such as upgraded biomass growth, process optimization, scale-up, and harvesting. Recently, researchers have discovered increasingly beneficial applications for MBC, including animal and aquaculture feed, fertilizer, and thermochemical conversion technologies. However, individuals utilizing microalgae and bacterial biomass must exercise caution regarding the waste they process and the potential pollutants that may accumulate within the biomass. This study discusses various projects worldwide in the MBC system and presents examples. This review also analyzes significant challenges and future formative research about proposals. Based on the study's results, we can guess what kinds of microalgae and bacteria are in the MBC system. The study gives us a solid foundation of information and theoretical guidance for improving and using the MBC system for treating wastewater. Overall, microalgae-bacterial consortia significantly improve nutrient removal performance in wastewater treatment systems.